The Role of Self-Efficacy and Competence in International Student’s Sociocultural Adaptation

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.23917/indigenous.v9i1.4124Keywords:

Self-Efficacy, Intercultural Communication, Sociocultural Adaptation, International Students, Japanese UniversityAbstract

This study examines the role of self-efficacy in intercultural communication as a mediator between competence perception and sociocultural adaptation among international students in Japan. The research uses a quantitative approach with convenience sampling technique, and obtains 92 international student participants. Several validated questionnaires are utilized, namely the Sociocultural Adaptation Scale (SCAS), a = 0.874 by Ward & Kennedy (1999) adapted by Simic-Yamashita & Tanaka (2010); Self-Efficacy in Intercultural Communication (SEIC) a = 0.914 by Peterson et al., (2011); Japanese Proficiency by Iwao & Hagiwara (1988); and Intercultural Communication Competence (ICC), a = 0.691 adapted by Gonçalves et al. (2020) from Arasaratnam (2009). A hypothesis model is constructed with competence perception as the predictor, self-efficacy as the mediator, and sociocultural adaptation as the dependent variable. Competence perception is a latent variable measured by two manifest variables: intercultural communication competence and Japanese language proficiency. Data analysis is conducted using Path Analysis, a form of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), with results indicating that the hypothesis model has an acceptable fit index. Although the proposed hypothesis model as a whole can be confirmed, a significant effect is found in the direct path between competence perception and sociocultural adaptation, while the indirect path is not significant. This means that self-efficacy does not act as a mediator, but rather as a predictor in sociocultural adaptation. The practical implications of this study emphasize the importance of stakeholders, such as international offices at universities, paying attention to the role of language proficiency, intercultural communication competence, and self-efficacy in international migrant students, especially in taking preventive or curative actions for adaptation problems.

INTRODUCTION

Recent studies have consistently highlighted the significant challenges faced by international students, surpassing those encountered by domestic students (Andrade, 2006; Kusek, 2015; Brunsting et al., 2018). Loneliness, social acceptance, and adapting to university demands are particularly sensitive for international students (Andrade, 2006). Moreover, international students often grapple with stress and anxiety in academic and social spheres (Ramsay et al., 2007 & Fritz et al., 2008).

However, most research on international student challenges is concentrated in English-speaking countries, leaving a substantial research gap in non-English-speaking countries (Ikeguchi, 2012; Tamaoka et al., 2003; Murphy-Shigematsu, 2002). This gap is particularly relevant for countries like Indonesia, which are non-English speaking and are witnessing a surge in migrant students. Addressing this gap can provide valuable insights into the adaptation patterns of migrant students.

One of the famous educational destinations for non-English speakers on the Asian continent is Japan. The number of international students in Japan significantly increases from year to year. In 10 years (2009-2019), international students in Japan experienced a significant increase, doubling from 132,720 to 312,214 people (JASSO, 2019). Despite this, research surrounding the issue of international student adjustment in Japan is still minimal. Even Lee (2017) stated that there was almost no research highlighting the context of international students in Japan in the Journal of International Students. International students still focus on Western countries as their favorite higher education destinations, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, etc. Apart from that, the urgency of research related to the context of international students in Japan is also supported by research conducted by (Kono et al., 2015) that the mental health of international students in Japan should be a significant concern because of the large prevalence of depression in international students which has reached 41%.

Japan, with its high-context culture, presents several cultural complexities that can challenge the adaptation of international students. For instance, the strong culture of shodan-shogi (group consciousness) fosters exclusive groups or communities for Japanese people, making it difficult for immigrants to assimilate (Lee, 2017). Government policies for international students, which primarily focus on academic programs by facilitating learning in full English at various universities in Japan, often overlook the need for cultural adjustment accommodations. This approach can inadvertently divide international and local students in Japan, leading to isolation among international students (Jiang et al., 2017 & Simic-Yamashita and Tanaka, 2010; Takamatsu et al., 2021).

Research by Murphy-Shigematsu (2002) also discussed the difficulty of interacting with

Japanese people for international students from Korea because of the gap between true feelings (honne) and formal behavior shown in public (tatemae). Even though Japan and Korea have similar cultures, they are still perceived as lacking sincerity and even offensive. Another international student from Peru also needed help understanding the concepts of honne and tatemae. He disliked this concept because it was difficult to understand Japanese people who did not show their thoughts (Lagones, 2019).

Students who emphasize the importance of transparent communication tend to think that Japanese people's communication needs to be more indirect and clear. Even students who understand the emphasis on non-verbal communication in the Japanese community still need help understanding it. Although it is understood that Japanese people value harmony in relationships more than honesty of expression, international students still need help to accept and view this culture as dishonesty. Other research also stated that as many as 81% thought that Japanese was difficult to use and understand, 75% said it was difficult to make friends with Japanese people because they did not show their true feelings, and 55% believed that Japanese people did not like foreigners (Ikeguchi, 2012). Based on the social problems mentioned, the author considers that there is an urgency to conduct further research regarding the adaptation of international students in Japan.

Facing the problems of migrating to a new country, good adaptation output is essential for international students to optimize migration's positive impact. The term adaptation for immigrants is divided into two, namely sociocultural adaptation and psychological adaptation. Sociocultural adaptation refers to the practical and behavioral aspects of adapting to a new culture; this aspect attempts to navigate culture more effectively in daily life. Sociocultural adaptation is divided into three domains: academics, daily life, and interpersonal relationships (Simic-Yamashita & Tanaka, 2010). Meanwhile, psychological adaptation refers to a person's comfort, happiness, anxiety, and alienation in a new culture. These two dimensions must be measured independently because although they are related, they are different constructs and do not always correlate (Ward et al., 1999; Motti-Stefanidi., 2008).

Fundamental factors such as destination country language proficiency and broader communication competence are also determinants of sociocultural adaptation because they are beneficial for successful social interactions (Masgoret & Ward, 2012). Meanwhile, Wilson (2013) underlined the importance of paying attention to context regarding the association of language with sociocultural adaptation. In contrast to immigrants from Asian countries, English-speaking Western countries have more opportunities to understand and participate in society, considering that English acts as a lingua franca.

Interpersonal relations are the most challenging subdomain for immigrants (Ma, 2015). Interpersonal relationships are closely related to individual communication abilities, so an effective form of communication is needed that is deemed appropriate in displaying accepted and expected behavior in a particular context. According to Arasaratnam (2009), accepted behavior depends on the cultural context or relationships that must consider the intercultural context. The ability to predict an individual's contact with others from different cultures is called intercultural communication competency. Intercultural Communication Competency is the insight, motivation, and skills to interact effectively and appropriately with people from different cultures (Wiseman, 2002). In the cultural learning paradigm, there is an emphasis on the importance of identifying intercultural communication. For example, after immigrants arrive in a new culture, immigrants will become unfamiliar with the social interaction patterns of that culture. They will not be socially skilled in the communication differences they experience (Wilson, 2013). Individuals who can realize and understand these differences in intercultural communication are believed to be able to quickly develop specific cultural skills in navigating intercultural situations (Furnham & Bochner, 1982).

Japan is ranked 80th out of 110 countries on the English Proficiency Index and is categorized as very low (EF et al., 2022) even though Japan is, in fact, a developed country. The pedagogical aspect of TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) or Teaching English as a Foreign Language in Japan has failed and has received much criticism due to the entrance exam system and the large number of incompetent teachers (Hashimoto, 2009; Deacon & Miles, 2023). Japan's late steps in the curriculum area also drew criticism from many Western researchers due to the Japanese government's bureaucracy and the xenophobic attitude of Japanese society itself (Goodman, 1990). This homogeneity in the use of Japanese as the only national language used by Japanese society means that it creates urgency for international students living in Japan to be able to master Japanese in order to adapt to where they are. As stated in previous research, proficiency in a particular language cannot be denied as having relevance in communication competence with others who also speak that language (Arasaratnam-Smith, 2016). The effectiveness of intercultural communication will be more accepted in a context where the individual has mastery of the language appropriate to that context as a medium for immigrants to adapt. In the cultural learning paradigm, there is an emphasis on the importance of identifying intercultural communication. After immigrants arrive in a new culture, they will become unfamiliar with the social interaction patterns of that culture and will not appear socially in the communication differences they experience (Wilson, 2013). Individuals who can realize and understand the differences in intercultural communication are believed to quickly develop specific cultural skills in navigating intercultural situations (Furnham & Bochner, 1982).

Intercultural Communication Competence consistently predicts adaptation (Zimmerman, 1995; Gritsenko et al., 2021). However, both the language competence of the destination country and broader communication competence are fundamental factors for the effectiveness of social interaction with the output of sociocultural adaptation (Masgoret & Ward, 2012). Researchers see intercultural communication and language competence in the destination country as conditions for forming individual competence, with competence as one component of SDT (Self-Determination Theory). The concept of perceived competence itself departs from SDT, which tries to explain that motivation arises from essential psychological satisfaction (competence, autonomy, and relatedness) (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Perceived competence refers to an individual's expectations of success, defined as subjective beliefs about the capability to perform a particular task successfully (Cho et al., 2011). Perception of competence is related to exposure to knowledge and experience that individuals have acquired and learned.

Apart from perceptions of competence related to an individual's previous abilities, self- efficacy is also a relevant topic for examining the focus area of communication competence (Kabir & Sponseller, 2020). The concepts of self-efficacy and perceptions of competence promote behavioral engagement, learning, and the acquisition of specific skills. However, theoretical self- efficacy does not address the expected consequences of successful behavior and will only motivate behavior when the required skills already exist (Markland et al., 2014). Self-efficacy departs from Bandura's SCT (Social Cognitive Theory) construct, which defines self-confidence in specific situations (Bandura et al., 1999). Bandura stated that the source of self-efficacy is mastery experiences. This experience is indicated through the capabilities and competencies perceived to be mastered by the individual. Kabir and Sponseller (2020) showed that intercultural competence and perceptions of the effectiveness of communication skills are identical in their measurement. This means that intercultural competence and intercultural effectiveness are identical constructs. In their research, intercultural effectiveness (as a construct that is considered synonymous with intercultural competence) has a significant positive relationship with intercultural communication self-efficacy with r = 0.40 (Kabir & Sponseller, 2020).

Previous studies have also proven a relationship between self-efficacy and sociocultural adaptation with r = 0.45 (Wilson & Fischer, 2013). Research from Grisentko et al. (2021) shows that self-efficacy has a more significant effect in predicting adaptation than other variables, such as the stability of cross-cultural communication. By paying attention to the large effect size of self-efficacy on sociocultural adaptation, which is dominant compared to other variables, as well as the relationship between perceived competence and intercultural self-efficacy, as explained in the previous paragraph, the researcher wants to find out more about whether self-efficacy can be a mediator between an individual's perceived competence (perceived competence/perceived competence) towards sociocultural adaptation. The researcher also wanted to test suggestions from previous researchers who stated that there are still few studies that test self-efficacy and one aspect of SDT (perceived competence) simultaneously, which causes the possibility of misinterpreting the idea that these two constructs are similar because the concepts of both tend to be repeated (Markland et al., 2014). Researchers will use perceived competence as a latent variable from two manifest variables: 1) second language proficiency, in this case Japanese; 2) intercultural communication competence.

The major hypothesis in this research is a relationship between perceived competence and sociocultural adaptation mediated by intercultural communication self-efficacy. The major hypothesis can be specified into several minor hypotheses, namely: a) there is a relationship between perceived competence and sociocultural adaptation; b) there is a relationship between perceived competence and intercultural communication self-efficacy; c) There is a relationship between intercultural communication self-efficacy and sociocultural adaptation.

METHOD

The research design employed in this study is quantitative research with a cross-sectional survey design. This design is particularly relevant as it allows for data collection at a specific time, thereby enabling the examination of the relationship between variables at that particular moment.

The participants in this study were selected based on several criteria: They were immigrants from various countries, not Japanese citizens, and were or had been on temporary visa status in Japan as university students. Importantly, they were not native Japanese speakers. The participant pool was diverse, with 28 participants (30.43%) from individualistic countries and 64 participants (69.57%) from collectivistic countries, as categorized based on Hofstede's (1980) literature. The data was collected through online questionnaires distributed from September 5, 2022, to November 4, 2022.

The sample size for this study was determined using the A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models from Daniel Soper (Cohen, 1988; Westland, 2010; Soper, 2023). The anticipated effect size at level 0.1 (power = 0.8; alpha = 0.05; latent variable = 1; observed variable = 4) indicated a minimum sample of 87 participants. The sampling technique used was convenience sampling, resulting in a total of 92 participants. The survey was conducted using an online questionnaire distributed via various platforms, including social media, instant messaging applications, and direct visits to universities in Japan. Ethical considerations were upheld through the provision of informed consent to participants.

Research hypotheses are divided into two, namely, major and minor. The major hypothesis of this research is that there is a relationship between perceived competence and sociocultural adaptation, mediated by intercultural communication self-efficacy. The minor hypothesis is specified as a) there is a relationship between perceived competence and sociocultural adaptation; b) there is a relationship between perceived competence and intercultural communication self-efficacy; c) There is a relationship between intercultural communication self-efficacy and sociocultural adaptation.

To test the research hypothesis, the authors recruited 92 participants (age = 23.6; SD age

= 3.87; 52.2 percent female) who were international students in Japan. Participants consisted of students with full-time status (55.4%) and exchange students (44.6%). Most participants had never taken the JLPT or Japanese Language Proficiency Test (56.5%), N5 category (7.6%), N4 category (5.4%), N3 category (4.3 %), category N2 (14.1%), category N1 (12%).

The Socio-Cultural Adaptation Scales (SCAS) instrument from Simic-Yamashita & Tanaka (2010), which consists of 25 items, was used to measure sociocultural adaptation. This instrument is an adaptation of the Ward & Kennedy (1999) scale, which previously consisted of 40 items. Items in this scale have been adapted based on relevance to the context of international students in Japan. This measuring tool uses a Likert Scale where participants are asked to rate a statement with a score of 1-5 that describes the difficulties experienced in Japan (1 = No difficulty, 5 = Very difficult) - instrument reliability a = 0.87.

The Self-Efficacy in Intercultural Communication scale (Peterson et al., 2011) consists of 34 self-report items to measure self-efficacy related to intercultural communication. This measuring tool uses a Likert scale with a score range of 1-7 (1 = not good at all and 7 = very good). The results of reliability analysis with Cronbach's alpha were 0.91.

The Japanese Proficiency instrument, which consists of 12 items compiled by Iwao and Hagiwara (1988), was used to measure participants' perceptions of Japanese Language Proficiency. Participants are asked to answer yes and no to several behavioral statements that they can carry out. A "yes" score is given 1 point, and a "no" score is given 0 points. The reliability analysis results using the Kuder Richardson-21 technique were 0.95.

Furthermore, to measure Intercultural Communication Competence, the Intercultural Communication Competence instrument was adapted by Gonçalves et al. (2020) from Arasaratnam (2009). Initially, this scale had ten items, but it was revised to 8 items in the latest version Gonçalves et al. (2020). This scale can be defined multidimensionally with the following three dimensions: affective, behavioral, and sociocognitive. Apart from that, Goncalves also sees this instrument as two properties that can be seen on a global scale or unidimensionally (Goncalves, 2020). This instrument uses a Likert Scale where participants are asked to rate a statement with a score of 1-7, which describes the difficulties experienced (1 = do not agree at all, 7 = strongly agree). Reliability analysis results in a = 0.69.

All questionnaires were measured for content validity using the Content Validity Index (CVI) before data collection by two experts who are native English speakers. The CVI scores on this instrument are intercultural communication competence = 0.958, sociocultural adaptation = 966, intercultural communication self-efficacy = 0.995, and Japanese proficiency = 1.

This research uses Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis techniques to analyze the relationship between measurable and latent variables. The application used in this research is Jamovi version 2.3.21.0. The estimation method and Standard Error (SE) parameters used are ML (Maximum Likelihood).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results of the assumption test in this study show that the residuals are normally distributed based on the Q-Q Plot and the Shapiro-Wilk test (W = 0.978, p > 0.05), and homoscedasticity is fulfilled through the residual plot graph and the Breusch-Pagan test (p = 0.233). There was no significant autocorrelation (Durbin-Watson = 1.96), and multicollinearity was not a problem, with VIF values ranging from 1.07 to 1.12 and tolerance values ranging from 0.892 to 0.938. All basic assumptions for regression analysis have been met, validating the use of the regression model in this research.

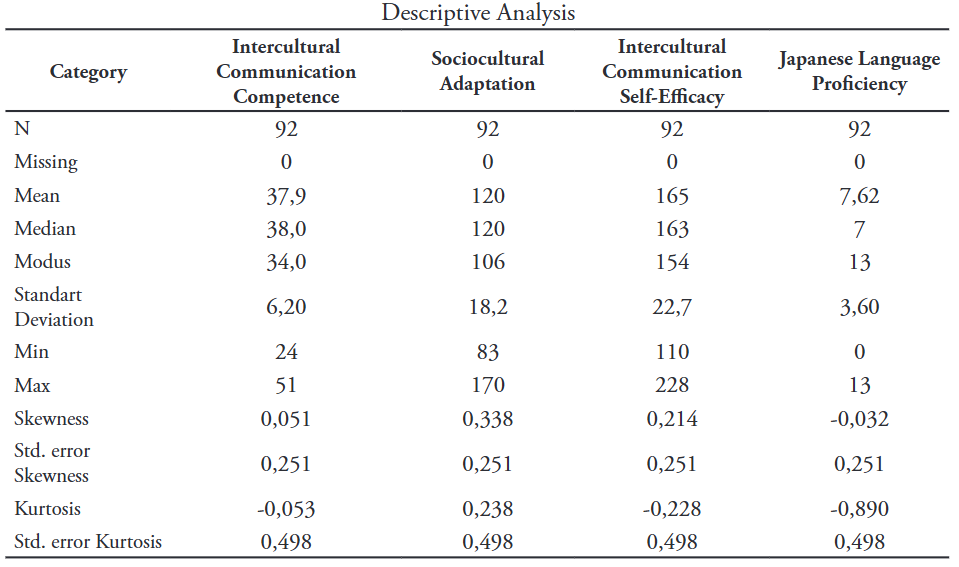

To strengthen the results of this descriptive data analysis based on the result in Table 1, a difference test analysis was carried out using the t-test on the main variables between collectivistic and individualistic countries. The results showed there was no significant difference between Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy (p=0.078; Cohen's d=0.403), Intercultural Communication Competence (p=0.242; Cohen's d=-0.267), and Japanese Language Proficiency (p=0.202; Cohen's d=0.291 ). However, there were significant differences in sociocultural adaptation p=0.046, Cohen's d=0.458; collectivistic mean = 122; individualistic mean = 113.79).

Based on the results of the zero-order correlation test in Table 2, it is known that: a) there is a significant positive correlation between Intercultural Communication Competence and Japanese Language Proficiency (r = 0.248; p < 0.05); b) there is a significant positive correlation between Sociocultural Adaptation and Japanese Language Proficiency (r = 0.332; p < 0.05); c) there is a significant positive correlation between Intercultural Communication Competence and Sociocultural Adaptation (r = 0.266; p < 0.05); d) there is a significant positive correlation between Intercultural Communication Competence and Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy (r = 0.242; p <0.05);

e) there is a significant positive correlation between Sociocultural Adaptation and Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy (r = 0.558; p <0.05); There is no significant correlation between Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy and Japanese Languange Proficiency (r = 0.114; p> 0.05).

Table 1.

Descriptive Analysis

The SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square) indicator underscores our model's suitability, with a value of 0.032, well below the cut-off of 0.08. Additionally, the CFI index, a key measure of model fit, yielded a result of 0.971. According to Hooper, Coughlan, and Mullen (2008), a CFI value ≥ 0.95 is considered a strong fit. These results affirm that our theoretical model or hypothesis aligns well with the observed data which mention on the Table 2.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlation Analysis Results

*Note:sigp<0.05

Figure 1, factor loading of the Japanese Languange Proficiency variable = 0.56; Intercultural Communication Competence = 0.44 on the Perceived Competency variable. This shows that the latent variable Perception of Competence can explain the variables of Japanese Languange Proficiency Intercultural Communication Competence as indicators of this latent variable. Meanwhile, the contribution of the variable (unstandardized regression) Perceived Competence to the relationship to Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy = 0.32 and Sociocultural Adaptation = 0.46. Then, the role of Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy on Sociocultural Adaptation = 0.41. The overall factor loading value meets the threshold value criteria > 0.3 (Tavakol & Wetzel, 2020).

Perceived Competence plays a significant role in predicting Sociocultural Adaptation (B

=0.465; CI95 [0.159; 0.769]), p = 0.047. However, it does not significantly predict Intercultural Communication self-efficacy (B = 0.323 (CI95 [0.0103; 0.636]), p = 0.107). On the other hand, intercultural Communication self-efficacy is a strong predictor of sociocultural adaptation (B =

0.408 (CI95 [0.181; 0.634]), p < 0.01). This suggests that the direct relationship (X --> Y) is more influential than the indirect relationship (X-->M-->Y).

While minor hypotheses H1 (a) and H1 (c) have been confirmed to have a significant direct influence, the non-confirmation of H1 (b) leads to the conclusion that the major hypothesis is not supported by the data. In other words, our findings indicate that Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy does not mediate the relationship between Perceived Competence and Sociocultural Adaptation.

Figure 1.

Path Diagram

The research results based on Figure 1 show that Perceived Competence and Self-Efficacy in Intercultural Communication can predict adaptation. The significance of the positive relationship between Perceived Competence and Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy indicates that international students tend to be able to adapt if they believe that they have capabilities in specific competencies, which in this case are intercultural communication competency and second language skills. As explained in a previous study by Masgoret and Ward (2012), language competence in the destination country and broader communication competence are determinants of sociocultural adaptation. In line with previous research, this research shows a significant influence of Perceived Competence on Sociocultural Adaptation. This relationship makes sense because second language skills and intercultural competence reflected in cross-cultural empathy, experience, motivation, attitudes, and active listening can speed up a person's adjustment when living in a new culture.

However, instead of being a mediator of adaptation, Self-Efficacy in Intercultural Communication has a role as a predictor with the most significant effect size. This is indicated by the relationship between Perceived Competence and Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy, which is insignificant.

Table 3.

Hypothesis test parameter estimation (95% Confidence Interval)

However, the relationship between intercultural communication self-efficacy and sociocultural adaptation is significant that mention on Table 3, with an effect size much more extensive than that of PC. This finding contrasts with previous research, which states that intercultural effectiveness, defined as an individual's overall competence when interacting with other individuals from different cultures, is moderately positively related to Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy (Kabir & Sponseller, 2020). Our research implicitly shows that when international students feel they have specific competencies (which in this research are reflected in the variables of intercultural communication competence and second language ability), then they do not necessarily have the self-confidence (self-efficacy) to succeed in the scope of intercultural communication. Several things could cause the insignificant relationship between Perceived Competence and Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy: 1) differences in collectivism-individualism culture; 2) traits. Both are possible and could impact the relationship pattern of Perceived Competence with Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy.

Although this research proves that there is no significant effect between Perceived Competence and Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy, this research supports previous studies that claim a significant relationship between self-efficacy and adaptation (Wilson & Fischer, 2013). Apart from that, this research is also in line with research by Zhang & Goodson (2011), which supports social self-efficacy as a predictor of well-being related to international student adjustment. Self-efficacy is a stable trait that is not easily affected by the stress of cross-cultural travel (Tsai et al., 2016). Self- efficacy is a potential strategy to reduce the risk of loneliness for Chinese international students in the United States, considering that it is also stated that international students can experience loneliness because they struggle to develop new relationships and face challenges related to building a supportive environment in a new environment (Hayes & Lin, 1994). As well as in other recent cases, self-efficacy has consistently been proven to be a protective factor against loneliness (Ramos, 2022). Several studies (Oettingen, 1995; Ahn et al., 2016; Bonneville-Roussy, 2019) say that students in collectivistic countries tend to assess self-efficacy in academic contexts lower than in individualistic countries. Specifically, even Ahn et al. (2016) showed lower self-efficacy and higher anxiety in students from collectivistic countries compared to students from individualistic countries in the context of study participants from Korea, the Philippines, and the United States.

Meanwhile, the majority of participants in this research came from collectivistic countries (69.57%) and individualistic countries (30.43%). However, there is no significant difference in Intercultural Communication self-efficacy between countries that are assumed to be collectivistic and individualistic. This also provides insight into the fact that individualism and collectivism are not only issues of national boundaries but also refer to more complex issues, such as whether one lives in a rural or urban area. For example, in the United States, there is a general pattern of relative collectivism in the Southern United States (Hawaii, Louisiana, South Carolina) compared to the Great Plains and Mountain West (Montana et al.), which tend to be individualistic (Vandello & Cohen, 1999 ). In this study, researchers did not ask about specific regional origins (rural or urban) in the demographic questionnaire, so conclusions about individualistic and collectivistic cultures would tend to be overgeneralized and too heterogeneous if they only relied on categories based on nationality. Also mentioned in Lee et al. (2010) that to better understand individual unique characteristics related to cultural and social comparisons, researchers should also evaluate the effects of individualism-collectivism with more reliable instruments than assuming that individuals from the same country have the same cultural value orientation.

Our research also points to the need for future studies to consider additional factors that may influence self-efficacy, such as personality traits. Judge et al. (2007) have suggested that the predictive validity of self-efficacy diminishes significantly when individual difference factors are considered. In particular, the traits of conscientiousness and neuroticism from the Big Five theory have been identified as consistent predictors of self-efficacy. Conscientiousness promotes task engagement and effort, thereby increasing self-efficacy, while neuroticism, associated with anxiety, can reduce self- efficacy (Schmitt, 2008; Brown et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2019). Therefore, future research should consider controlling for sociodemographic factors (such as ethnic differences) and specific personality traits (neuroticism and conscientiousness) to understand self-efficacy more comprehensively.

CONCLUSION

This study answers various possible assumptions about the psychological mechanisms that play a role in sociocultural adaptation. The magnitude of the effect of self-efficacy on sociocultural adaptation in several studies (e.g., Wilson & Fischer, 2013; Grisentko et al., 2021) as well as the relationship between perceptions of the effectiveness of intercultural competence on intercultural communication self-efficacy (Kabir & Sponseller, 2020), turns out to be inadequate in creating efficacy. Themselves as appropriate and significant mediators. This is assumed to occur due to cultural differences in collectivism-individualism and personality traits.

Future research needs to use individualistic vs collectivistic socio-demographic variables, primarily rural vs urban, and trait factors (conscientiousness and neuroticism) to clarify the relationship between Perceived Competence and Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy. These variables can be considered moderator variables in the model on the relationship between Perceived Competence and Intercultural Communication Self-Efficacy. In addition, further testing could also be carried out to implement the paradigm in this research in migrant populations other than international students, such as expatriates and refugees in non-English speaking countries. In the future, policymakers such as the international office need to facilitate the needs of international students regarding adaptation issues through training or classes on specific abilities that adapt to the cultural context of the country where migrant students reside.

References

Ahn, H. S., Usher, E. L., Butz, A., & Bong, M. (2016). Cultural differences in the understanding of modeling and feedback as sources of self-efficacy information. The British journal of educational psychology, 86(1), 112–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12093 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12093

Andrade, M. S. (2006). International students in English-speaking universities: Adjustment factors. Journal of Research in International Education, 5(2), 131-154. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1475240906065589 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240906065589

Arasaratnam, L. A. (2009). The Development of a New Instrument of Intercultural Communication Competence. Journal of Intercultural Communication, 9(2), 1–08. https://doi.org/10.36923/jicc.v9i2.478 DOI: https://doi.org/10.36923/jicc.v9i2.478

Arasaratnam-Smith, L. A. (2016). An exploration of the relationship between intercultural communication competence and bilingualism. Communication Research Reports, 33(3), 231-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2016.1186628 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2016.1186628

Bandura, A., Freeman, W. H., & Lightsey, R. (1999). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 13(2), 158. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158

Bonneville-Roussy, A., Bouffard, T., Palikara, O., & Vezeau, C. (2019). The role of cultural values in teacher and student self-efficacy: Evidence from 16 nations. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 59, 101798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101798 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101798

Brown, S. D., Lent, R. W., Telander, K., & Tramayne, S. (2011). Social cognitive career theory, conscientiousness, and work performance: A meta-analytic path analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.11.009 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.11.009

Brunsting, N. C., Zachry, C., Takeuchi, R. (2018). Predictors of undergraduate international student psychosocial adjustment to US universities: A systematic review from 2009-2018. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 66, 22-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.06.002 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.06.002

Cho, Y. J., Weinstein, C. E., & Wicker, F. (2011). Perceived competence and autonomy as moderators of the effects of achievement goal orientations. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology, 31(4), 393-411. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2011.560597 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2011.560597

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Deacon, B., & Miles, R. (2023). Toward better understanding Japanese university students’ self-perceived attitudes on intercultural competence: A pre-study abroad perspective. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 16(3), 262-282. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2022.2033813 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2022.2033813

Fritz, M.V., D. Chin, dan V. DeMarinis. (2008). Stressors, Anxiety, Acculturation and Adjustment Among International and North American Students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 32 (3), 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.01.001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.01.001

Furnham, A., & Bochner, S. (1982). Social difficulty in a foreign culture: An empirical analysis of culture shock. Cultures in contact. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-025805-8.50016-0

EF Education First. (2022). EF english proficiency index - Japan (2022). Retrieved from https://www.ef.com/assetscdn/WIBIwq6RdJvcD9bc8RMd/cefcom-epi-site/fact-sheets/2022/ef-epi-fact-sheet-japan-english.pdf

Kono, K., Eskandarieh, S., Obayashi, Y., Arai, A., & Tamashiro, H. (2015). Mental health and its associated variables among international students at a Japanese University: With special reference to their financial status. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(6), 1654- 1659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0100-1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-0100-1

Goodman, R. (1990). Japan's ‘international youth’: The emergence of a new class of schoolchildren. Oxford University Press.

Geeraert, N., Li, R., Ward, C., Gelfand, M., & Demes, K. A. (2019). A Tight Spot: How Personality Moderates the Impact of Social Norms on Sojourner Adaptation. Psychological Science, 30(3), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618815488 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618815488

Gonçalves, G., Sousa, C., Arasaratnam-Smith, L. A., Rodrigues, N., & Carvalheiro, R. (2020). Intercultural Communication Competence Scale: Invariance and Construct Validation in Portugal. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 49(3), 242-262. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2020.1746687 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2020.1746687

Gritsenko, V. V., Khukhlaev, O. E., Zinurova, R. I., Konstantinov, V. V., Kulesh, E. V., Malyshev, I. V., Novikova, I. A., & Chernaya, A. V. (2021). Cross-cultural competence as a predictor of adaptation of foreign students. Cultural and historical psychology, 17(1), 102–112. https://doi.org/10.17759/chp.2021170114 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17759/chp.2021170114

Hayes, R. L., & Lin, H.-R. (1994). Coming to America: Developing social support systems for international students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 22(1), 7–16. http://doi.org/10.1002/j .2161-1912.1994.tb00238.x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.1994.tb00238.x

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage Publications.

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53-60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

Hashimoto, K. (2009). Cultivating "Japanese Who Can Use English": Problems and Contradictions in Government Policy. Asian Studies Review, 33(1), 21-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357820802716166 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10357820802716166

Ikeguchi, C. (2012). Internationalization of Education & Culture Adjustment The Case of Chinese Students in Japan. Intercultural Communication Studies, 21(2). https://www-s3-live.kent.edu/s3fs-root/s3fs-public/file/10CeciliaIkeguchi.pdf

Iwao, S., & Hagiwara, S. (1988). Foreign students studying in Japan: Social psychological analysis. The Keiso Shobo.

Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO). (2021). International students in Japan in 2019. retrieved from: https://www.studyinjapan.go.jp/en/_mt/2020/08/date2019z_e.pdf

Jiang, X. ., Yang, X. ., & Zhou, Y. (2017). Chinese international students’ perceptions of their language issues in U.S. universities: A comparative study. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 6(1), 63–80. Retrieved from https://www.ojed.org/index.php/jise/article/view/1760

Judge, T. A., Jackson, C. L., Shaw, J. C., Scott, B. A., & Rich, B. L. (2007). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: The integral role of individual differences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.107 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.107

Kabir, R. S., & Sponseller, A. C. (2020). Interacting With Competence: A Validation Study of the Self-Efficacy in Intercultural Communication Scale-Short Form. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2086. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02086 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02086

Kim, Y. Y. (1991). Communication and Cross-Cultural Adaptation. In L.A. Samovar & R.E. Porter (Eds.), Intercultural Communication: A Reader, Sixth edition. Wadsworth.

Kusek, W. A. (2015). Evaluating the Struggles with International Students and Local Community Participation. Journal of International Students, 5(2), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v5i2.429 DOI: https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v5i2.429

Lagones, J. (2019). Academic and Daily Life Satisfaction of Monbukagakusho Scholarship Students in Japan: The Case of Peruvians as International Students in Japan. Asian Social Science, 15(9), 53-66. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v15n9p53 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v15n9p53

Lee, J. (2009). Universals and specifics of math self-concept, math self-efficacy, and math anxiety across 41 PISA 2003 participating countries. Learning and Individual Differences, 19(3), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2008.10.009 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2008.10.009

Lee, C. T., Beckert, T. E., & Goodrich, T. R. (2010). The relationship between individualistic, collectivistic, and transitional cultural value orientations and adolescents’ autonomy and identity status. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(8), 882–893. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9430-z DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9430-z

Lee, J. S. (2017). Challenges of international students in a Japanese university: Ethnographic perspectives. Journal of International Students, 7(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v7i1.246 DOI: https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v7i1.246

Ma, Y., & Wang, B. (2015). Acculturation Attitudes and Sociocultural Adaptation of Chinese Mainland Sojourners in Hong Kong. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 6(6), 69-73. https://journals.aiac.org.au/index.php/alls/article/view/1856 DOI: https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.69

Markland, D. A., Rodgers, W. M., Markland, D., Selzler, A., Murray, T. C., & Wilson, P. M. (2014). Distinguishing Perceived Competence and Self-Efficacy: An Example From Exercise. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85(4), 527-539. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.961050 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2014.961050

Masgoret, A.-M., & Ward, C. (2012). Culture learning approach to acculturation. The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511489891.008 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489891.008

Murphy-Shigematsu, S. (2002). Psychological barriers for international students in Japan. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 24(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015076202649 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015076202649

Motti-Stefanidi, F., Pavlopoulos, V., Obradović, J., & Masten, A. S. (2008). Acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents in Greek urban schools. International Journal of Psychology, 43(1), 45-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701804412 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701804412

Nguyen, M. H., Le, T. T., & Meirmanov, S. (2019). Depression, Acculturative Stress, and Social Connectedness among international university students in Japan: A statistical investigation. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030878 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030878

Oettingen, G. (1995). Cross-cultural perspectives on self-efficacy. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511527692.007

Onishi, A. (2016). Campus internationalization and counseling services for international students: developing culturally competent services for students. University of Tokyo Press. https://doi.org/10.5926/arepj.56.165 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5926/arepj.56.165

Onwumechilia C., Nwosub P., Jackson R., James-Hughes J. (2003). In the deep valley with mountains to climb: Exploring identity and multiple reacculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(02)00063-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(02)00063-9

Oscarson, M. (1989). Self-assessment of language proficiency: rationale and applications. Language Testing, 6(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/026553228900600103 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/026553228900600103

Peterson, J. C., Milstein, T., Chen, Y. W., & Nakazawa, M. (2011). Self-efficacy in intercultural communication: the development and validation of a sojourners’ scale. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 4(4), 290–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2011.602476 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2011.602476

Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T., & Owen, S. V. (2007). Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in nursing & health, 30(4), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20199 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20199

Ramsay, S., Jones, E., & Barker, M. (2007). Relationship between Adjustment and Support Types: Young and Mature-Aged Local and International First Year University Students. Higher Education, 54(2), 247–265. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29735109 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9001-0

Royce, J. R. (1963). Factors as theoretical constructs. American Psychologist, 18(8), 522–528. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044493 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044493

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.55.1.68

Schmitt, N. (2008). The interaction of neuroticism and gender and its impact on self-efficacy and performance. Human Performance, 21(1), 46-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959280701522197 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08959280701522197

Simic-Yamashita, M., & Tanaka, T. (2010). Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Sociocultural Adaptation Scale (SCAS) among International Students in Japan. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 29, 27-38. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/12535572.pdf

Spitzberg, B. H., & Changnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence. SAGE. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071872987.n1

Stajkovic, A. D., Bandura, A., Locke, E. A., Lee, D., & Sergent, K. (2018). Test of three conceptual models of influence of the big five personality traits and self-efficacy on academic performance: A meta-analytic path-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 120, 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.014 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.014

Soper, D.S. (2023). A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models [Software]. retrieved from: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc

Takamatsu, R., Min, M. C., Wang, L., Xu, W., Taniguchi, N., & Takai, J. (2021). Moralization of Japanese cultural norms among student sojourners in Japan. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 80, 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.12.001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.12.001

Tamaoka, K., Ninomiya, A., & Nakaya, A. (2003). What makes international students satisfied with a Japanese university?. Asia Pacific Education Review, 4, 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03025354 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03025354

Tavakol, M., & Wetzel, A. (2020). Factor Analysis: a means for theory and instrument development in support of construct validity. International journal of medical education, 11, 245–247. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5f96.0f4a DOI: https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5f96.0f4a

Tatsuya, I. (2020). What Helps International Students Disclose Themselves and Be Assertive to Host Nationals for Their Cultural Adjustment?: Focusing on Languange Proficiency and Length of Stay. Japanese Journal of Communication Studies, 49(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.20698/comm.49.1_5

Tsai, W., Wang, K. T., & Wei, M. (2017). Reciprocal relations between social self-efficacy and loneliness among Chinese international students. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 8(2), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000065 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000065

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2021). Internationally mobile students. In UIS Glossary of Education Terms. retrieved from: https://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/internationally-mobile-students

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2019). International Migration 2019. retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/migrationreport/docs/InternationalMigration2019_Report.pdf

University World News. (2012). New UNESCO interactive map on global student mobility. http://retrieved from: www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=201211021435243

Vulić-Prtorić, A. i Oetjen, N. (2017). Adaptation and Acculturation of International Students in Croatia. Collegium antropologicum, 41(4), 335-343. retrieved from: https://hrcak.srce.hr/205231

Ward, C., Bochner, S., & Furnham, A. (2001). The psychology of culture shock (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1993). Psychological and socio-cultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions: A comparison of secondary students overseas and at home. International Journal of Psychology, 28(2), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207599308247181 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00207599308247181

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1999). The measurement of sociocultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23(4), 659–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(99)00014-0 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(99)00014-0

Westland, J.C. (2010). Lower bounds on sample size in structural equation modeling. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 9(6), 476-487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2010.07.003 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2010.07.003

Wilson, J. K. (2013). Exploring the past, present, and future of cultural competency research: The revision and expansion of the sociocultural adaptation construct. retrieved from: http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/2783%5Cnhttp://hdl.handle.net/10063/2783

Wiseman, R. L. (2002). Intercultural communication competence. In W. B. Gudykunst & B. Moody (Eds.), Handbook of international and intercultural communication (2nd ed.). Sage.

Wilson, J., Ward, C., & Fischer, R. (2013). Beyond Culture Learning Theory: What Can Personality Tell Us About Cultural Competence?. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(6), 900–927. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113492889 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113492889

Yeh, C. J., & Inose, M. (2003). International students’ reported English fluency, social support satisfaction, and social connectedness as predictors of acculturative stress. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 29(3), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.0.4.56/0951507031000114058 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0951507031000114058

Zhang, J., & Goodson, P. (2011). Predictors of international students’ psychosocial adjustment to life in the United States: A systematic review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(2), 139–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.11.011 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.11.011

Zimmermann, S. (1995). Perceptions of intercultural communication competence and international student adaptation to an American campus. Communication Education, 44(4), 321-335. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529509379022 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529509379022

Submitted

Accepted

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2024 Rakhman Ardi, Mutia Az Zahra

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.