Early Childhood Self Regulated Learning Based on Javanese Local Wisdom Jawa

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.23917/indigenous.v9i1.2652Keywords:

Children, Java, Self Regulated LearningAbstract

Abstract. The study describes early childhood self-regulated learning (SRL) based on the Javanese philosophy in Ki Hadjar Dewantara (KHD) & Ki Ageng Suryamentaram (KAS) concepts. This used a phenomenological qualitative approach on 6 subjects (3-5 years old) dyadic with their mothers in Yogyakarta. The main data were collected through interviews, participant observation, and supported by data of the children’s developmental maturity by filling out the Temperament Assessment Scale, Child's behavior and SDIDTK checklists. Data analysis techniques were carried out by organizing data, grouping based on themes and answer patterns, testing existing assumptions or problems with the data, writing research results. The results showed that the SRL in line with the process of ‘Free Spirit’ of the 6 subjects varied and contained dynamic abilities in their process. The environment (parents/family) had not consistently implemented SRL in their ‘Among’ (Asah Asih Asuh & Ing Ngarsa Sung Tulada) and Kawruh Pamamong (Ngulawantah-lare/regulating children) systems. The ability of SRL subjects to understand (Ngerti Sumerep), to feel (Ngrasa Sih) and to action (Nglakoni Nrimo) still had no clear pattern on subjects. The internalization of SRL was in the process of co-regulatory behavior.

INTRODUCTION

The ability to control oneself, known as self-regulated learning, has an important role in individual development. Having self-regulated learning will help children develop themselves in academic and social achievements. Self-regulated is not acquired coincidentally but taught gradually starting from the family environment.

Self-regulated learning (SRL) is ensued from an interdependent causal structure from personal, behavioral, and environmental aspects. Self-regulated learning (SRL) is a process of reconstructing oneself so that she/he possesses more skilled will and mental abilities in an activity (Bandura, 2001; Dinata et al., 2016; Zimmerman, 1989).

Furthermore, Zimmerman & Martinez-Pons (1990) affirm that SRL engages metacognition, motivation, and behavior that actively participates in the learning process. Baumert et al., (2000) suggest that self-regulated learning is also defined as an individual learning process upon learning motivation so that someone autonomously develops measurements (cognition, metacognition, and

monitors his/her learning progress.

Based on this explanation, it implies that displaying self-regulated learning will improve action independence. The cultivation of self-regulated learning diverts children to be able to regulate or control their actions, distinguishing between what is right and what is wrong. Self-regulated is important for children in the millennial era and is a never-ending process (long life learner).

Developing self-regulated learning from an early age is the key to successful development in adulthood. Lack of quality early learning will lead children and this nation to problems in the future. This is evident from the high rate of child violence (as victims and perpetrators), the Indonesian Child Protection Commission (Komisi Perlindungan Anak Indonesia, hereafter abbreviated as KPAI) discovered that only 27.9% of fathers and 36.6% of mothers sought quality learning information premarriage. As many as 66.4% of fathers and 71% of mothers only copied the learning they had learned from both their parents, from generation to generation (Nurcaya, 2015).

Why is early childhood learning so vital? Early childhood of 1 - 6 years is a golden, sensitive, susceptible, and sensitive period in establishing the basics of personality, reasoning abilities, inner intelligence, and social skills and abilities (Novrinda et al., 2017). According to Ki Hajar Dewanta (2013), early childhood education is a responsive period in a child's life, a moment when the child's enthusiasm is agape to all the experiences received, becoming the foundation of a permanent soul, which adds to the content of the spirit, not changes the foundation of the spirit. This learning model is adapted to the child's developmental stages.

The learning process for early childhood is essential, in which the development of language skills, creativity, social awareness, motor skills, and cognitive and emotional progress is very rapid. As a matter of fact, every child is born with respective distinctive characteristics according to one’s nature. Early childhood learning plays a significant role in social relationships and improving the quality of life starts to develop after birth (Ilgar & Karakurt, 2018; Khadijah, 2016).

Obviously, when it comes to early childhood education, the family environment with parents at the center has a major role. Education in the family greatly determines the success of independent self-regulation in the future. A family tailored by parents can ideally provide the basis for learning character, ethics, aesthetics, affection, security, rule-abiding, and good manners (Widianto, 2014).

Children's development and abilities are the result of the process of learning something from the environment, especially the family (Gagne in Gunarsa, 2014). In the family, parents become models for children (early age) to imitate. Children's perceptions tend to recognize, accept, and imitate which will later become part of their personality. The socialization process occurs either directly or indirectly in interaction with the family environment. Parents act as teachers (leaders of ethics), as teachers (leaders of intelligence and providers of knowledge), and as examples of social behavior (Suparlan, 2016).

Ki Hajar Dewantara emphasizes that the family dynamic wise becomes a character learning process for young children. Character learning begins from the moment the child is born, intensively and consistently building strong and orderly intelligence in accomplishing personality or soul character. Education in the family was conceptualized by Ki Hajar Dewantara in the "Among"system and the "Kawruh Pamomong" concept from Ki Ageng Suryomentaram (Kusnandar, 2010; Subur & Syauqi, 2022; Suryomentaram, 1989).

The family accompanies and governs children in learning their cultural values conveniently. Early childhood education aims to spruce up the mind, educate the heart (sensitivity of conscience), and improve skills as a form of liberating the soul. Ki Hajar Dewantara's educational concept is

freedom of spirit which implies that it is a gift from God to humans by bestowing them the right to govern themselves (zelfbeschikkingsrecht). So it can be concluded that self-regulated learning corresponds with 'free spirit' education or learning (Lickona, 1986; Muti.ah, 2018).

Self-regulated learning is fundamental in the socialization process for children in Ngerti,Ngrasa, Nglakoni (Understanding, Feeling, Acting) and also involves Asuh, Asah, and Asih (providing affection, stimulating potentials, fulfilling the needs) (Papalia, et al., 2008; Muti'ah, 2018). Children with a high level of self-regulation will have proper control in achieving their goals (Schunk and Zimmerman in Ropp, 1999). Self-regulated learning in Javanese philosophy refers to the concepts of Ki Hadjar Dewantara (KHD) and Ki Ageng Surmetaram (KAS). KHD with the Among system highlights that children are given freedom as long as it is safety, volunteerism, democracy, tolerance, order, peace, suitability to circumstances, according to their level of development, and avoiding orders and coercion (Dewantara, 2013).

Meanwhile, Ki Ageng Suryomentaram with KawruhPamomongin RaosPsychology functions to regulate/educate children (nggulawentah lare) (Sugiarto, 2015; Suryomentaram, 1989). According to Muniroh (2018), KAS suggests three main principles in educating children:

1) teaching children to sumerep (comprehend and understand), parents to teaching children to understand things accordingly for them to think appropriately. 2) teaching children to love other people so they do not belittle others and be arrogant towards others. This will allow children to be able to reach a strong condition and develop a sense of love for others. 3) Teaching children to love beauty, which cultivates a sense of love for the beauty of all things. Five aspects that can optimize the process are pangganda (smell), pamireng (hearing), pandulu (sight), pangrasa (taste), and panggrayang(touch).

In Javanese philosophy and culture, children's learning is carried out not based on their wishes or will but on Javanese philosophy, cultural values, and traditions. Children's learning patterns in Javanese culture are interrelated to influences including parental age (maturity), extended family engagement, parental education, parenting experience, and family harmony. Children's learning is inseparable fromsocialandcultural activities (Baiduri& Yuniar, 2017; Ekaet al., 2007; Vgotsky, 1978).

Self-regulated learning has been in the discourse of many researchers. Research by Azhari et al. (2023) and Khoiriyah et al. (2021) shows that the role of parents is correlated with the development of self-regulated learning among children. Meanwhile, research by Saa’da (2021) shows that cultural background influences the formation of self-regulated learning. These studies have not described how cultural background is applied to self-regulated learning in families during early childhood.

This research aims to determine the description of self-regulated learning for early childhood based on Javanese philosophy (Javanese culture). Children's self-regulated learning can be implemented from an early age and comes simultaneously with the child's immediate environment, namely parents and family in the philosophical and cultural contexts of Among and KawruhPamamong.

Javanese cultural values are compatible with character formation in children. Philosophy is useful for alleviating humans from identity loss. Character formation is also greatly influenced by the cultural philosophy behind it. Therefore, it is important to embed cultural philosophy in education, both formal and informal. KHD and KAS have laid the foundation for the education world of Indonesia which is heavily embellished by Javanese culture amidst the strong penetration of Western concepts. Studies that implement ideas originating from Indonesian culture are a big advantage because they will reduce the deviation of existing variables (Gularso et al., 2019; Wicaksono et al., 2016).

METHOD

This research was conducted in Yogyakarta, with a qualitative phenomenological approach (Denzin et al., 2004; Poerwandari, 1998). The focus of this research is to understand the meaning of self-regulated learning in early childhood based on Javanese philosophy through learning patterns from parents (especially mothers) as the developers of the child's learning environment. Javanese philosophy-based self-regulated learning is intended to describe: 1) nature in the Javanese family setting; 2) Among(Ngemong)and KawruhPamamong(Ngulawentahlare)learning patterns on the subject in the family setting; 3) the learning process of children's self-regulation in Ngerti/Sumerep(ability/knowledge) – Ngrasa/Sih(will) – Nglakoni/Nrimo(act earnestly and accept it); (4) ultimate goal of self-regulated learning (free spirit) is the child's habituation and behavior. The subjects of this research consisted of 6 children aged 3-5 years and their parents (mother-child dyadic), in which parents were first asked to fill out several checklists to explore the child's description using; the Indonesian version of the Temperament Assessment Scale for Children and the SDIDTK Book or known as Stimulation, Detection, Early Intervention of Growth and Development from the Ministry of Health (2016) according to age.

Research data were obtained through in-depth interviews (semi and unstructured), and observation (open and participant). The scientific validity of research data was carried out to maintain the credibility and dependability of the data by implementing the triangulation method through subjects and/or significant others of neighbors, close family, friends, and playground teachers.

Data analysis techniques were carried out by organizing data, grouping based on themes and answer patterns, testing existing assumptions or problems with the data, and describing research results. Researchers refer to several stages of analysis from (Miles et al., 2018), namely: reducing data, displaying data, analyzing data, and drawing conclusions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ilgar & Karakurt (2018) emphasize that early childhood is the period when children begin to use mental strategies to control their impulses, emotions, and thoughts; and behave according to social and ethical values to direct their thoughts and behavior in fulfilling personal goals and the expectations of others. Self-regulated learning in early childhood among Javanese families is characterized by culture, instilling Javanese values, morals, and ethics.

Table 1.

Research Subjects

The results of the 'Self-Regulated Learning for Early Childhood Based on Javanese Philosophy'

research on the 6 subjects and their mothers through interview and observation methods are described in table 1.

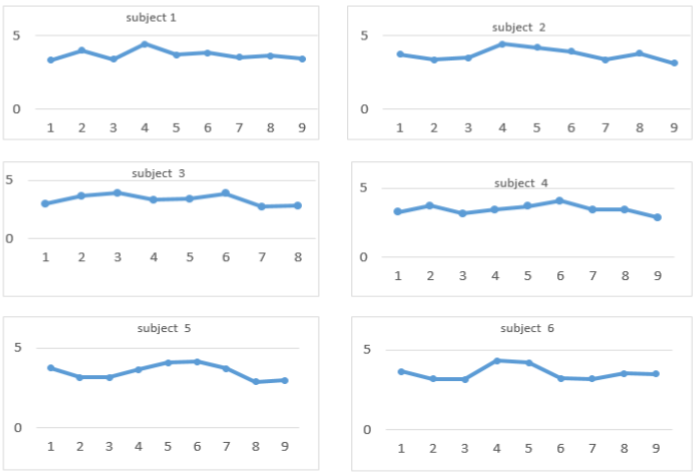

This study measured children's temperament using a temperament assessment scale as well (Figure 1). The temperament scale has 9 dimensions, namely, Activity, Rhythmicity, Approach, Adaptability, Intensity, Mood, Persistency, Distractibility, and Threshold. Thefollowingisadescription of children's character as measured using the temperament assessment scale (Muti'ah, 2012).

Figure 1.

Character of Subject is Measured Using Temperament Assessment Scale

The overall natural description/nature of the subjects suggests the accumulation of natural or genetic factors (temperament, nature, character) from the parents and nurture factors or learning/ experience/habits from the child's environment. The description of the overall cognitive and language development of the subjects on average shows a high level of intelligence, creativity, and a high sense of curiosity, active speaking or questioning except for S3 and S4 who appeared to be quiet. Participants S3 and S4 did not respond to their surrounding environment but to their toys.

S3whenbeingaskedbytheresearcher....whatareyouplayingwith...(quiet)Thetoyslookgood ( quiet), when the mother asked him to take a bath...(quiet). S4 responded withoutwordswhentheresearcheraskedandaskedforatoy.TheattitudeofS4towardsherparentstendedtobe'sengol'(passive-aggressive).(Obs.S3/S4)

The character and temperament development is closely related to the parenting style applied to children. Parents with a democratic parenting style effectively, such as giving freedom while still obeying the applicable rules, allow children to feel trusted and more appreciated, thus making them

better at expressing anger well. Parents of permissive parenting effectively will make children feel independent and trusted, which later affects their temperament. Children will be obedient and will not like to defy. Parents who implement an authoritarian parenting style effectively will create a good temperament because of such a pattern, namely by providing strict sanctions if the children flout (Dwi et al., 2021).

The social-emotional abilities of all subjects developed rather properly and corresponded to their age maturity. Although there were variations in the social-emotional abilities shown by the subjects. Family or parental background will influence their development that mention in Table 2. This includes economic conditions (Atika & Rasyid, 2018; Nurwati & Listari, 2021), single parents (Anggraini et al., 2020; Purwati et al., 2020), parents with adverse event (Amiruddin, 2021).

Table 2.

Family Background and Children's Socio-emotional Abilities

All subjects at an early age possessed a picture of parenting and learning from the environment

that shapes their character and behavior. The diversity of the subject's natural character developed and changed along with the conditions and situations occurring within parents and families. This greatly influenced the subject, including the initial commitment when the subject's parents established a family and the environmental context in which the subject grew up. Although there were several similarities in the overall nature of the subject (1-6) with various talents, sensitivity was very high when interacting with the immediate psycho-social and cultural environment. Among them; S1 had dominant physical talents and skills and was smart in kindergarten; S2 was talkative, asked questions, and teased the researcher to keep on playing and be near him; S3 and S4 were good and stealth observers; S4 was very intelligent, was talkative and took care of her brothers and sisters; Meanwhile, S6 was good at speaking and singing even though she was rather selfish when the researcher responded to her younger sibling. On the other hand, it is undeniable that the subject's habit (S1, S3, S4, S6) was to hold and use gadgets quite skillfully because they imitated the behavior of parents/siblings/close people to them who intensively used gadgets.

The cognitive abilities of all subjects were very good according to their development (even on average exceeding the age), as expressed by the many questions raised by the subjects even though their language or vocabulary was limited. On average, all subjects responded to the researcher when observing, showed how to play something, told something, responded, immediately protested if not responded to, displayed dissatisfaction, and were honest, open, and very sensitive.

Table 3.

Family Background and Children's Socio-emotional Abilities

Among four subjects (S1, S2, S3, S6) of lone or the first-born, S1 and S6 appeared to be selfish, more sensitive, attention-seeking, and prone to tantrums (demanding, angry, whining, and crying) to the point of forcing their parents to fulfill their wishes but not to anyone else. Meanwhile,

S2 and S3, as the lone children, also showed selfish behavior, sought for attention (from researchers), and were spoiled, dominated, and controlled situation/their parents based on the result in Table 3. From the data, it can be inferred that parents, especially the mothers, did not understand the subjects’ developmental and maturity stages, and were still burdened with their problems. Besides, the parents were not prepared to be good and ideal models/role models for the subjects. Parents prioritized the children's physical/material needs rather than their future independence. Hence, subject learning in forming children's self-regulation abilities was hampered and not delivered

effectively.

The psycho-social-cultural environment in which the subject interacts becomes a medium for very effective and intensive self-regulated learning. All subjects come from Javanese families and are accustomed to Javanese learning patterns that have been passed down for generations. Self- regulated learning cannot be isolated from Javanese cultural habits and philosophy (Figure 2). The family or parents as guardians are responsible for parenting or education or learning the subjects (Baiduri & Yuniar, 2017; Eka et al., 2007; Vgotsky, 1978).

Figure 2.

Self Regulated Learning in Javanese Philosophy

Self-regulated Learning (SRL) refers to Javanese philosophy and culture and can be implemented specifically in early childhood. A significant aspect in establishing SRL refers to the teachings of Ki Ageng Surya Mentaram, namely Momong/AmongorPamamong(Ngulawantahlare).

Parents should cultivate SLR subjects when they are under five so that children can ngerti(sumerep),ngrasa(sih)dannglakoni(nrimo)(Gularso et al., 2019; Sugiarto, 2015).

The principles in kawruh pamomong are important to teach to children at an early age as they have an extraordinary interest in the outside world. The age of 1 - 6 years is a golden, susceptible, and sensitive period in establishing the basics of personality, reasoning abilities, inner intelligence, and social skills and abilities (Novrinda et al., 2017)

The application of these three principles undergoes two stages. The first is by teaching or studying the three principles above through knowledge level. At this stage, the knowledge gained will be juxtaposed with what is within oneself. In such circumstances, differences will usually appear. However, the differences must be controlled for them not to provoke self-righteousness, avoiding misunderstandings. The second stage is practicing by applying, experiencing, feeling, and researching what has been obtained in the first stage. The application is carried out by correcting personal notes, thoughts, and ideas and then examining the feelings of other people as examples of oneself. The final step is to apply it in daily life (Sugiarto, 2015).

The role of parents, in this case, is indeed substantial. The subjects’ parents are the main environment in SRL in the Javanese tradition. On the other hand, parents' mistakes and ignorance in Momong, Pamamong, or implementing Asah Asih Asuh in early childhood could affect the development of the children’s character in the later stage (Lickona, 1986; Muti'ah, 2018). The results of the research suggest that the parents had not been equitable in providing models or role models for subjects. This resulted in obstacles for their children. Some of the behaviors are not having a good level of decision-making, being spoiled, showing tantrums, being impulsive, whining, irritating, and dependent.

The SRL ability of the subject in Ki Hadjar Dewantara's concept of building an 'free spirit' and the concept of Ki Ageng Suryamataram as 'nggulawentah lare' (self-regulating) was found to be in process and developing gradually in the subjects through Among and Pamamong. Parents or families should be oriented towards learning or educational targets and achievements that liberate the subject's soul according to age. The subject's self-regulated learning ability will succeed if the ability to Ngerti or Sumenep is fulfilled (understanding is cultivated/internalized), Ngrasa or Sihmaturity (be able to motivate oneself), and Nglakoni or Nrimo ability (independent behavior and humility). The learning of Free Spirit and Nggulawentah lare was conveyed to the subjects through environmental conditioning (parents/family) in implementing Ing Ngarso sungtulada (consistent modeling/role model).

SRL on participants was applied and the process was embedded in their spirits, reflected in quite orderly, assertive, creative, attached, empathetic, and independent attitudes as well as behavior. The parents (father and mother) of all subjects attempted to be consistent and orderly and continuously cooperated to develop the process of self-regulated learning or liberating children's souls using the Among and Kawruh Pamamong methods passed down for generations among Javanese families. Parents and adults (grandmothers, uncles, aunts) as the main environment for subjects who effectively employ the Amongand Pamamongmethods will provide development space for children in carrying out more complex developmental tasks. Eventually, the subjects will be able to organize the incoming information, choose the right and positive response, and actively participate in every situation or event. Until the time comes, subjects can consistently regulate themselves independently without parents and internalize the self-regulated 'free spirit'. The Among and Pamamong systems will facilitate the subjects to develop this skill and a free spirit in all aspects of their progress. Meanwhile, insufficient parents and environments to apply the Among and Pamamong system to children will hamper the process of liberating the child's spirit and subsequent development.

CONCLUSION

The study of self-regulated learning for early childhood based on Javanese philosophy (Javanese culture and traditions) on 6 subjects with their parents (especially mothers) suggested varying stages and was still in process or development. The implementation of the Among system (Asah Asih Asuh & Ing Ngarsa Sung Tulada) and Kawruh Pamamong (Ngulawantah lare/regulating children) in liberating their minds (Ngerti,Sumerep), spiritual (Ngrasa,Sih) and behavior (Nglakoni,Nrimo) in SRL had not been implemented effectively on the subject.

Self-regulation learning or the subject's 'free spirit' process was dominantly determined by how consistent and effective parents or adults in the subjects' learning environment implemented the Amongand Pamamongsystems which are deep-rooted in Javanese culture. This research shows that the mother's role was more dominant (2 single mother subjects) in the subject's self-regulated learning than the father's. Learning also became less centered, yet it aimed at the children’s future needs due to the involvement of the extended family (grandparents, uncles, or aunts), which can result in positive or negative effects. Subjects’ learning had not been addressed at the formation of the ‘free spirit' that the subjects urgently need in the future. Subjects will later learn to understand, respond appropriately, and delay/control desires, actively participating in every learning situation or situation. Parents are expected to be able to become models/role models and consistently tailor the self-regulated learning environment of children’s early childhood. Subjects will become more accustomed to self-regulated learning without the assistance of their parents/other people and independently internalize the self- regulation of 'free spirit' (Ngerti/Sumerep,Ngrasa/Sih,Nglakoni/Nrimo).The internationalization of self-regulated is a process, in which the subjects' co-regulated behavior increases from their parents

to independent behavior.

References

Amiruddin, H. S. (2021). Hubungan kehamilan Ibu di usia muda dengan perkembangan emosi anak Usia 3-5 tahun di wilayah kerja puskesmas Ibrahim Adjie Kota Bandung. Jurnal Sehat Masada, 15(1), 162–168. doi: 10.38037/JSM.V15I1.175 DOI: https://doi.org/10.38037/jsm.v15i1.175

Anggraini, H., Amir, A., & Maputra, Y. (2020). Hubungan pola asuh orang tua tunggal Ibu dengan kematangan emosi dan keterampilan sosial pada anak pra sekolah usia 4-6 tahun di PAUD kecamatan Koto Tangah kota Padang tahun 2019. Jurnal Kesehatan Andalas, 8(4). doi: 10.25077/JKA.V8I4.1127 DOI: https://doi.org/10.25077/jka.v8i4.1127

Atika, A. N., & Rasyid, H. (2018). Dampak status sosial ekonomi orang tua terhadap keterampilan sosial anak. Pedagogia : Jurnal Pendidikan, 7(2), 111–120. doi: 10.21070/pedagogia.v7i2.1601 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21070/pedagogia.v7i2.1601

Azhari, S. C., Fadjarajani, S., & Rosali, E. S. (2023). The Relationship Between Self-Regulated Learning, Family Support and Learning Motivation on Students’ Learning Engagement. Journal of Education Research and Evaluation, 7(1), 147–158. doi: 10.23887/JERE.V7I1.52481 DOI: https://doi.org/10.23887/jere.v7i1.52481

Baiduri, R., & Yuniar, A. (2017). Pola pengasuhan keluarga etnis Jawa hasil pernikahan dini di Deli Serdang. Jurnal Antropologi Sumatera, 15(1), 252–258. doi: 10.24114/JAS.V15I1.8624

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory and clinical psychology. In N. Smelser, J & B. Baltes (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01340-1

Baumert, J., Klieme, E., Neubrand, M., Prenzel, M., Schiefele, U., Schneider, W., Tillmann, K., & Weiss, M. (2000). Self-Regulated learning as a cross-curricular competence konsortium. OECD PISA.

Denzin, N. K., Lincoln, Y. S., Giardina, M. D., & Cannella, G. S. (n.d.). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. SAGE Publications.

Dewantara, K. hajar. (2013). Bagian pertama: Pendidikan pemikiran, konsepsi, keteladanan, sikap merdeka. Majelis Luhur Persatuan Tamansiswa.

Dinata, P. A. C., Rahzianta, R., & Zainuddin, M. (2016). Self regulated leraning sebagai strategi membangun kemandirian peserta didik dalam menjawab tantangan abad 21. Prosiding SNPS (Seminar Nasional Pendidikan Sains), 139–146. retrieved from: https://jurnal.fkip.uns.ac.id/index.php/snps/article/view/9829

Dwi, D., Ambali, W., Allo, L. B., Ta’diampang, B., Tinggi, S., Kesehatan, I., & Toraja, T. (2021). Hubungan pola asuh orang tua dengan temperamen anak usia sekolah kelas III di SD Kristen Toraja Sa,dan Matallo Kabupaten Toraja Utara tahun 2019. Jurnal Ilmiah

Kesehatan Promotif, 6(1), 89–103. doi: 10.56437/JIKP.V6I1.63 DOI: https://doi.org/10.56437/jikp.v6i1.63

Eka, R., Siti, I., Suardiman, P., Ayriza, Y., Hiryanto, P., & Kusmaryani, R. E. (2007). Perkembangan Peserta Didik. UNY Press.

Gularso, D., Sugito, & Zamroni. (2019). Kawruh pamomong: Children education based on local wisdom in Yogyakarta. Jurnal Cakrawala Pendidikan, 38(2), 343–355. doi: 10.21831/cp.v38i2.21556 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21831/cp.v38i2.21556

Gunarsa, S., & Gunarsa, Y. (2014). Psikologi perkembangan anak dan remaja. BPK Gunung Mulia.

Ilgar, S. M., & Karakurt, C. (2018). Importance of promoting self-regulatory abilities in early childhood period. Journal of Education and Practice, 9(12), 30–36. retrieved from: https://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEP/article/view/42199/43445

Khadijah. (2016). Pengembangan kognitif anak usia dini. Perdana Publishing.

Khoiriyah, S., Khilmiyah, A., & Fauzan, A. (2021). Effect of family support, learning strategies, and lecturer professional competence through self-regulated learning mediator on online learning motivation of FAI PTKIS students kopertais III Yogyakarta. Edukasia : Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan Islam, 16(2), 325–340. doi: 10.21043/edukasia.v16i2.11508 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21043/edukasia.v16i2.11508

Kusnandar. (2010). Guru profesional; implementasi kurikulum tingkat satuan pendidikan (KTSP) dan sukses dalam sertifikasi guru. Raja Grafindo Persada. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21009/JEP.022.05

Lickona, T. (1986). Educating for Character. Bantam.

Miles, M. B, Huberman A. M, & Saldana, J. (2018). Qualitative data analysis. SAGE Publication.

Muniroh, A. (2018). Kawruh pamomong Ki Ageng Suryomentaram: Prinsip-prinsip moral untuk untuk mengoptimalkan pendidikan empati pada anak. 2nd Proceedings of Annual Conference for Muslim Scholars: Kopertis wilayah 4 Surabaya. retrieved from: http://proceedings.kopertais4.or.id/index.php/ancoms/article/view/176

Muti'ah, T. (2018). Pola Asuh Aman: Secure Parenting Berbasis Konsep Asah Asih. Satunma Tamansiswa.

Novrinda, N., Kurniah, N., & Yulidesni, Y. (2017). Peran orangtua dalam pendidikan anak usia dini ditinjau dari latar belakang pendidikan. Jurnal Ilmiah Potensia, 2(1), 39–46. doi: 10.33369/JIP.2.1.39-46

Nurcaya, I. A. (2015). KPAI: Indonesia butuh pengasuhan berkualitas. Bisnis.com. retrieved from: https://lifestyle.bisnis.com/read/20150922/236/474930/kpai-anak-indonesia-butuh-pengasuhan-berkualitas

Nurwati, R. N., & Listari, Z. P. (2021). Pengaruh status sosial ekonomi keluarga terhadap pemenuhan kebutuhan pendidikan anak. Share : Social Work Journal, 11(1), 74–80. doi: 10.24198/share.v11i1.33642 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24198/share.v11i1.33642

Poerwandari, K. E. (1998). Pendekatan Kualitatif untuk Penelitian Perilaku Manusia. LPSP3 UI.

Purwati, A., Hafidah, R., & Pudyaningtyas, A. R. (2020). Pola pengasuhan orangtua tunggal terhadap pengaturan emosi anak usia 4-5 Tahun. Kumara Cendekia, 8(2), 116–125. doi: 10.20961/KC.V8I2.32300 DOI: https://doi.org/10.20961/kc.v8i2.32300

Saa’da, N. (2021). Parental involvement and self-regulated learning: The case of Arab learners in Israel. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 10(2), 1–26.

Subur, S., & Syauqi, C. (2022). The concept of Kawruh Jiwa and Pamomong in the perspective of Ki Ageng Suryomentaram. IBDA` : Jurnal Kajian Islam Dan Budaya, 20(1), 95–109. doi: 10.24090/IBDA.V20I1.6183 DOI: https://doi.org/10.24090/ibda.v20i1.6183

Sugiarto, R. (2015). Psikologi raos: Saintifikasi kawruh jiwa Ki Ageng Suryomentaram. Pustaka Ifada.

Suparlan, H. (2016). Filsafat pendidikan Ki Hajar dewantara dan sumbanganya bagi pendidikan Indonesia. Jurnal Filsafat, 25(1), 56–74. doi: 10.22146/JF.12614 DOI: https://doi.org/10.22146/jf.12614

Suryomentaram, K. A. (1989). Kawruh jiwa wejangan Ki Ageng Suryomentaram (Jilid 1). CV Hajimasagung.

Vgotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of the higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4

Wicaksono, D. E. & Priyanggasari, S. T. A. (2016). Kawruh pamomong KAS (Ki Ageng Suryamentaram): Nilai-nilai moral untuk optimalisasi bonus demografi. Psychology Forum UMM: Seminar Asean 2nd Psychology and Humanity, 95–101. retrieved from: https://mpsi.umm.ac.id/files/file/95101%20Dian%20Eko%20Wicaksono%20ok.pdf

Widianto, E. (2014). Transformative learning pengasuhan anak usia dini di lingkungan keluarga. Jurnal Pendidikan Humaniora, 2(2), 156–163. retrieved from http://journal.um.ac.id/index.php/jph/article/view/4455/936

Zimmerman. (1989). Self-Regulated learning and academic achievement: Theory, research, and practice. Spring Verlag Inc. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-3618-4

Zimmerman, B. J., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1990). Student Differences in self-regulated learning: relating grade, sex, and giftedness to self-efficacy and strategy use. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 51–59. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.51 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.82.1.51

Submitted

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2024 Titik Mutiah, Sulistyo Budiarto, Victor.A Pogadev

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.