BASELINE SURVEY OF TSANGAYA QUR’ANIC SCHOOLS IN TARABA STATE NIGERIA

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.23917/profetika.v25i01.4249Keywords:

tsangaya, qur'anic, education, muslims, taraba stateAbstract

This paper titled Baseline Survey of Tsangaya Qur’anic Schools in Taraba State is research on the various Tsangaya schools in Taraba State. The survey is a comprehensive mapping exercise on the existing traditional Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State to provide concrete and verifiable data on the Tsangaya (traditional Qur’anic schools) in the entire State. The generated data was tabulated and analyzed using simple percentages as the suitable statistical method of computing the findings. The major findings of the survey were analyzed, revealing 900 functional Tsangaya Schools and their respective proprietors. While 3,409 teachers were pencilled in, 61,882 enrollment figures were recorded in the survey. The carrying capacity of the schools across the State stands at 80,749, while the total enrollment as of the period covered by this survey is 61,882, showcasing a glaring gap of 18,867. Community goodwill and support were the most pressing peculiarly needs of Tsangaya Qur’anic schools, while sanitation represented the least on the list. Thereupon, recommendations on needful measures for effective mitigation of the plights of the traditional (Tsangaya) Qur’anic school system in Taraba State were proffered, stressing the perennial need for strategic intervention/investment in Tsangaya Qur’anic schools by all relevant bodies with the view to rewind-the-past-glory-of-the-system.

Tijjani Usman Karofi

Department of Islamic Studies, Taraba State College of Education Zing, Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

Education is aimed at building and growing an individual through training and skills and boosts the individual’s mind, intellect, and sense of reasoning. From an Islamic perspective, education is considered to be the way and manner in which individuals are nurtured; it is a process where individuals are built and nursed . Besides that, education in Islam was gained to actualize the perfections of an individual and essentially, to recognize the existence of Allah and His attributes. The importance of knowledge in Islam leads to the emergence and establishment of informal and formal education in the place of the spread of Islam, including Nigeria .

The history of Islamic education in Nigeria is synonymous with Islam in Nigeria, education has gone along with the religion in its initial stage. Education cannot do without religion neither religion can go without education [1]. The Prophet (peace be upon him), gives much emphasis on the quest for religion and he says, “If Allah wants to do good to a person, he makes him to understand the religion” . With the coming of Islam to Nigeria, the rulers of the Kanem Borno Empire accepted Islam and later employed teachers to teach the tenets of Islam to the communities . Islamic education in Nigeria was held as non-formally in the company of the teacher (Mallam). At that period, the students learn the Arabic text and the Qur’an, memorization of the Qur’an, and other basic teachings of the Islamic religion. It is mentioned here that there was not any form of government support or foreign aid to Islamic education at the time .

Tsangaya Qur’anic schools are the traditional basic Qur’anic education platforms in northern Nigeria saddled with teaching and learning the Qur’anic as a foundation of Islamic Education .

The system is a semi-formal structure, affordable and flexible, where a child is completely handed over to a Mallam (teacher) mostly to live in the Tsangaya (traditional Qur’anic school) within or away from the parents’ house, community, or village/town for full-time study of Qur’an .

Tsangaya Qur’anic schools are boarding-type; the students do not attend conventional primary schools. The schools are mostly located in the mallams’ (teachers’) homes or on the outskirts of the town with large numbers of children of 4-18 years age bracket. The schools can equally be found in or outside mosques, under the shade of trees, in open air, and in private houses .

Tsangaya is regarded as one of the main Islamic systems of education which has been developed in Nigeria. It is believed that the Tsangaya system has a long history of existence. Its origin can be traced to the old Timbuktu scholastic culture where Timbuktu, located in Western Africa in the Republic of Mali was the centre of Islamic education and Islamic scholarship . Many books were written and copied in Timbuktu starting from the 14th century. Besides that, the University of Timbuktu was established and later became well-known throughout the Islamic world. Thus, the spirit of old Timbuktu scholastic culture later influenced the emergence of the Tsangaya system of education in northern Nigeria. This system had over a long period graduated many Islamic scholars who later took the responsibility of teaching and spreading the religion of Islam nationwide. However, over time, the Tsangaya system has been encountering some problems that need the immediate or urgent attention of the government and the individuals to rescue. This old system of education is still very relevant for moral educational development in society .

Tsangaya refers to the informal school or place where teaching and learning of the Glorious Qur’an and other Islamic sciences takes place. The early Tsangaya schools were day institutions, that children attended from the comfort of their homes living with their families and receiving proper guidance, teaching, and learning . The word Tsangaya is derived from the Sangaya in Kanuri, which means educational institution . Consequently, Sangaya is the real name while Tsangaya is a Hausa alteration of the word. On the other hand, the term Tsangaya School known as Makarantar Allo derives its name from what is largely visible in the school which is the wooden slate Allo in the Hausa language. Apart from the general name, Tsangaya has other names such as Makarantar Muhammadiyya, Makarantar al-Qur’ani, Makarantar Toka, etc. Meanwhile, the word Almajiri is derived from the Arabic word Almuhajirun which means migrants. It refers to the students who enrol in the traditional method of acquiring and memorizing the Glorious Qur’an in Hausa land, it also refers to a particular place where children at their tender ages are sent out by their parents to other villages, towns, and cities for acquiring the knowledge of the Glorious Qur’an under the care of a knowledgeable Islamic scholar Alaramma, Mallam or Goni .

Qur’anic memorization and scholarship is a religious duty in Islam, a Qur’anic scholar is considered in Muslim societies as one of the noblest of men and is accorded much honour and respect. This position is not given to a Qur’anic scholar without a strong religious basis. It was reported from the Prophet (may peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) that:

The people of the Qur’an are men of Allah and his special people .

Allah in the Glorious Qur’an describes such people as those who constantly rehearse it, combined with the performance of daily Salat and giving charity secretly as those whose acts are equated with commerce that never fails. Allah promised to give them more of his bounties and complete their rewards. The Qur’an went further to describe those who inherit the Qur’an, the Ummah of Prophet Muhammad (may peace and blessings of Allah be upon him), as a selected community among the servants of Allah; this is a superior courtesy of the Qur’an, as contained in Surah al-Fāṭir: Verily, those who recite the Book of Allah (this Qur'an), perform AsSalat (IqamatasSalat) and spend (in charity) out of what we have provided for them, secretly and openly, hope for a (sure) trade gain that will never perish .

That He may pay them their wages in full, and give them (Even) more, out of his Grace. Verily! He is Oftforgiving, Most ready to appreciate (good deeds and to recompense). And in another verse of the same Surah, Allah also said: Then we gave the Book the Qur'an) for inheritance to such of Our slaves whom we chose (the followers of Muhammad Sal-Allaahu 'alayhe Wa Sallam). Then of them are some who wrong their selves, and of them are some who follow a middle course, and of them are some who are, by Allah's Leave, foremost in good deeds. that (inheritance of the Qur'an), that is indeed a great Grace .

In Taraba State, the historical setting of the Tsangaya tradition is organically linked with the evolution of Islam in the State . Therefore, the problem of this research lies in the lack of concrete and verifiable data on Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State. The aspiration of this research is, therefore, to provide a comprehensive database on Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State to facilitate policies and decision-making on matters about the system .

Literature Review

Preceding research has enlightened the historical background of the Tsangaya system of education and Islamic education in Northern Nigeria. The Islamic system of education is one of the two foreign systems of education that have significantly impacted the lives of the people of Nigeria. Many fields of discipline in Islamic sciences were thought of, this includes the Glorious Qur’an, Hadith, Fiqh, Sirah, and others fields . The system of Islamic education was developed and nurtured along with population growth in Nigeria, presently, there are Islamiyya schools, Tsangaya schools, and other Islamic teachers and preachers teaching and spreading Islamic education at different levels. Muhammad, Yusuf, and Bello stated that Tsangaya Qur’anic schools were well-known earlier the arrival of colonialism and their foot soldiers . Babajo, Jamaluddin, and Hamid corroborated that in many of the countries of West Africa, the Qur’anic schools had been well-known before the coming of the colonial masters to the shores of Africa .

Hoechner explained that the Tsangaya system of education has existed for many decades and that its historical development is traced since the early days of the coming of Islam to Nigeria. It has been observed that the system has been a basis for learning Islamic educational training for the dominant Muslim communities of Northern Nigeria . Consequently, Tsangaya as a system of education and learning can be dated back to the 11th century, when the Islamic Empires of Borno (1380s -1893) took charge of Qur’anic literacy, under the leadership of the then Shehun Borno El-Kanemi. The Borno Empire was a state in what is now north-eastern Nigeria, in time becoming even larger than Kanem Borno, incorporating areas that are today parts of Chad, Niger, Sudan, and Cameroon. Seven centuries later another Islamic state was founded in Sokoto, through a reformer and leader of the Sokoto Caliphate, Uthman bin Fodio (also known as Usman Dan Fodio) (1754-1817), establishing Islamic laws and teaching of the glorious Qur’an .

Hence, the aforementioned empires have introduced and established what is currently called the Tsangaya system of education . Young children often go to Tsangaya schools to learn daily comfortably from their homes and return when school hours are over. They happily live with their parents while receiving a good moral upbringing and guidance for further steps in life. Before the arrival of the British colonialists in the country, a lot of parents sent their children to the known as Makarantar Allo which refers to the curved wood object (slate) that the Qur’anic verse and chapters are written on and recited by the students .

Odumosu, Odekunle, Bolarinwa, & and Taiwo, observed that the creation of Qur’anic learning centers in the Northern part of the country happened at the beginning of the eleventh century . On their part, Babajo et al, the discussion centred on the establishment of the Tsangaya system of education in Northern Nigeria dating back to the colonial era. Ayuba argues that the Tsangaya system of education was initiated in the prophetic era . Equally, Adamu also hints at and highlights the development and establishment of the Tsangaya system of education by saying that the practice started as a result of the Da’wah of Prophet Muhammad (may peace and blessings of Allah be upon him). Moreover, Adamu also observes that the system of the Tsangaya learning in northern Nigeria has been divided into two; a basic level, which is called Kutb, and a more advanced level called Madrasa . Besides, he explains that the system of Tsangaya education is that it serves as a centre for the acquisition of knowledge whereby both the teachers and the students travel wide out of their places of origin and most cases stay there for a long period for recitation and memorization of the Glorious Qur’an .

Additionally, Jungudo exposed that after the colonial masters seized the mantle of leadership from the traditional rulers in the northern part of Nigeria, the system of Qur’anic education had lost the necessary care and power to stand on its own. Therefore, in some cases, the teachers send the students to work on farms or do other petty jobs, and others beg on the streets and get food as well as some money to pay the weekly dues while their counterparts in secondary schools are enjoying full support from the government. Usman relates that concerning the system of Tsangaya learning, the pattern and curriculum are normally limited to the recitation and memorization of the Glorious Qur’an .

METHODOLOGY

The research methodology adopted in this paper is a qualitative research approach. There are a variety of ways to collect data for survey-based research, the most popular of which are interviews and questionnaires. However, the primary data used for research is obtained through the field survey. Finding and gathering reference materials that are relevant to this research is the first of three processes the researcher adopted when putting this piece together .

The survey is descriptive research, entailing studying a situation in its natural setting with the view to generate data and analyze findings for decision-making. Accordingly, a survey study was employed owing to its advantage of focusing on the people or events and their sociological facts. Structured interview questions tailored to reflect the objectives, research questions, and hypothesis of the research were administered to Qur’anic school proprietors /teachers across the State. Thirdly, the researcher concludes the research by highlighting the outcome of the research for further study .

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

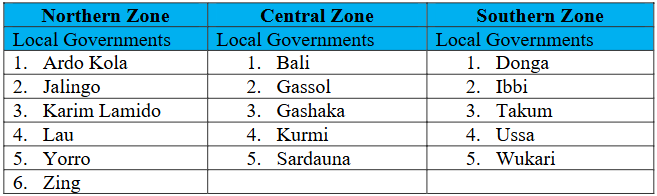

This survey was restricted to the typical Traditional Qur’anic schools (Tsangaya) where children are entrusted to a resident Malam (teacher) for full-time study of the Qur’an. The area of the study is Taraba State in northeastern Nigeria, which consists of three goe-political (senatorial) zones across the sixteen local government areas. Population and sample: the target population of the survey is the entire traditional Tsangaya Qur’anic schools of the Taraba State; hence, no sample was required.

Table 1. Showing Taraba State Geo-Political Zones and Local Governments

Source: Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette 2009

Research Question One: What is the actual number of functional Tsangaya Qur'anic schools in Taraba State?

Table 2. Functional Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State

Field Work: 2023

The above table reflected that nine hundred (900) widespread and well-developed Qur’anic schools and their educational excellence were found in Taraba State, with Bali and Gassol Local Governments topping the list. Situation appraisal in this survey revealed that the schools are found in or outside mosques, under the shade of trees, open air, and in private houses. Some Tsangaya schools in the state have a long history of existence spanning over a hundred years, with students as few as five and over 100 in other instances.

Research Question Two: What is the number of proprietors of Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State?

Table 3. Number of the proprietors of Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State

Field Work: 2023

From the data in Table 3, there are 900 proprietors of Qur’anic schools across the State, with 862 males and 38 females.

An important milestone revealed in this survey is the prevalence of female proprietors of traditional Qur’anic schools in the State. The ownership and mode of operation of Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State, as covered by this survey, depends on the discretion of an individual Malam (teacher). Most of the schools across the State are characterized by hereditary proprietorship, and a substantial number of the Tsangaya schools’ management are young entrepreneurs, which, according to Yunusa’s research, depicts a promising indicator for the system . The management structure of the schools is simple and often centred around the school proprietor, relying in most cases on irregular charitable sources for their upkeep and for operating the schools.

Research Question Three: What is the actual number of Tsangaya Qur’anic school teachers in Taraba State?

Table 4. Number of Tsangaya Qur’anic school teachers in Taraba State

Field Work: 2023

From Table 4 above, of the 3409 Tsangaya Qur’anic school teachers in Taraba State, 2715 are predominantly males, while 672 are females. From the table above, while Kurmi and Ussa Local Governments recorded the least male teachers, Gashaka and Zing Local Governments have the least number of female teachers. On the other hand, Gassol, Bali, and Jalingo are the leading Local Governments in the ranking.

Research Question Four: What is the enrollment figure of Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State?

Table 5. Enrollment figure of Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State

Source: Field Work: 2023

Table 5 portrays a staggering figure of 61,907 traditional Qur’anic school pupils in Taraba State, out of which 48,866 are males while 17,740 are females. A significant revelation in that direction is the existence of female Pupils (Almajirai) in the state who are hardly spotted in the available literature. Such pupils can never be seen on the streets but are confined within the residence of their respective proprietors, supporting the families with domestic functions. This is in line with Yunusa's findings in his research which factored social risk and cultural fractions as reasons for their exclusion.

The category of Qur’anic school pupils captured in this survey is the type that neither attends conventional primary schools nor is involved in any educational endeavour apart from full-time Qur’anic studies.

In Taraba State, Qur’anic school pupils (Almajiri), or the plural form Almajirai, in the context of the classical Qur'anic Schools system, are poor people by all common definitions. These studies revealed that a substantial number of Almajirai across the state came mainly from rural areas and from low-income family backgrounds, relying heavily on irregular charitable sources for their upkeep and operations. This is in line with Karofi. Accordingly, credible research equally portrays that the majority of the parents of the Almajirai (pupils) are from rural and semi-urban settings and have a low-income family background. Khalid. Being rural majority, Qur’anic school pupils were heavily under-represented in Western schools. Egalitarian posture and multiple entry points, among others, are the major drivers of the upscaled enrolment figures of Qur’anic schools .

Research Question Five: What is the carrying capacity of each Tsanngaya Qur’anic school in Taraba State?

Table 6. Enrolment Figures Vis-a-Vis Carrying Capacity of Each Tsangaya Qur’anic School in Taraba State

Source: Field Work 2023

From the above data, the carrying capacity of the schools across stands as 80,749 while the total enrollment as of the period covered by this survey is 61,882, showcasing a glaring gap of 18,867 between students’ enrolments and the carrying capacity of the Tsangaya schools in the State.

Accordingly, in most of the Tsangaya Qur’anic schools covered by this survey, classroom and hostel accommodation, especially for the pupils, are grossly adequate.

Research Question Six: What are the peculiar needs of Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in the State?

Table 7. Peculiarly Needs of Tsangaya Qur’anic Schools in Taraba State

Source: Field Work 2023

The above empirical records revealed the absence of instructional materials and the lack of infrastructural facilities. This is evidenced by the analysis of the particular needs of Qur’anic schools in Taraba State, entailing shelter, water, and sanitation, among others, with schools in urban areas being the most heated.

Similarly, sustainable financial base and remuneration for teachers were virtually absent in the majority of the Qur’anic schools covered by the survey in Taraba State.

The survey further revealed, among others, a diminishing communal commitment from the larger society coupled with a manifestation of a lack of political will by governments at all levels. The pupils largely depend on themselves for food, clothing, and sustenance.

The following are the findings of the research:

- There are 900 functional Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State.

- There are 900 proprietors of Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State, with 862males and 38 females.

- The number of teachers at Tsangaya Qur’anic schools in Taraba State stands at 3,409, with 2,715 males and 672females.

- The total enrollment figures of Tsangaya Qur’anic schools across Taraba State are 61,882, with 48,866 boys and 17,740girls

- The carrying capacity of the functional Tsangaya Qur’anic in schools in the state is 80,749, with a glaring difference of 18,867 against the total enrollment.

- Community goodwill and support were the most pressing peculiarly needs of Tsangaya Qur’anic schools, while sanitation represented the least

CONCLUSION

Addressing the plights of Tanagaya Qur’anic schools is a shared responsibility, requiring a comprehensive and sustainable reorientation, stimulating multi-sectorial engagements to neap the lingering challenges with the view to ensure effective value-chain and meeting the ever-changing scenarios of human life. This survey hopes that the findings should be taken with all sense of seriousness and that the recommendations made should be implemented with an appropriate dose of sincerity and greater commitment.

Based on the findings of this research, the following recommendations are proffered:

- There is a need for strategic intervention/investment in Qur’anic schools by all relevant bodies with the view to rewinding the past glory of the system.

- The National Commission of Almajiri Education is the boldest landmark with the core mandate to navigate an inclusive and quality Qur’anic education contextually and flexibly. The new commission has the crucial role of ensuring the involvement of critical stakeholders of the Tsangaya tradition through a bottom-top approach in determining policies, practical strategies, and decision-making on Qur’anic education in Nigeria.

- An ambitious regulatory framework on Tsangaya Schools is required to profile the schools, their location, capacity, itineracy facilities, etc.

- For effective Qur’anic education delivery, appropriate feedback mechanisms should be enforced. This is through routine inspection, quality monitoring, and evaluation, stating benchmarks or baseline standards to ensure the attainment of high standards.

- Qur’anic education delivery is a collective responsibility of community leaders, traditional rulers, parents, organizations, and other members of the general public. Hence, there is a need for appropriate solidarity and community goodwill.

- The Taraba State government should commit more resources to the development of Qur’anic education to complement the intervention models provided by the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC).

- A substantial percentage of budgets earmarked for Basic Education in the Taraba State should be channelled to registered/accredited Qur’anic schools to edge out the swelling figure of out-of-school children in Nigeria.

- Spirited efforts, donor partners, and philanthropic high-net-worth individuals should be encouraged to open their humanitarian corridors in supporting Qur’anic education delivery.

The author would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their assistance in improving the quality of research documents.

The author contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper, some are as chairman, member, financier, article translator, and final editor. All authors read and approved the final paper.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

A. Haque, “Psychology from Islamic perspective: Contributions of early Muslim scholars and challenges to contemporary Muslim psychologists,” J. Relig. Health, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 357–377, 2004, doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-004-4302-z.

I. Nadifah, N. Fauziah, D. A. Dewi, and U. P. Indonesia, “Membangun Semangat Nasionalisme Mahasiswa,” IJOIS Indones. J. Islam. Stud., vol. 2, no. 02, pp. 93–103, 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.59525/ijois.v2i2.30.

A. K. Hs, “Kurikulum Pendidikan Agama Berbasis Multikultura,” Al Marhalah | J. Pendidik. Islam, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 17–24, 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.38153/almarhalah.v3i1.28.

H. Cahyono, “Pendidikan Multikultural Di Pondok Pesantren : Sebagai Strategi dalam Menumbuhkan NilaiKarakter,” At-Tajdid J. Pendidik. dan Pemikir. Islam, vol. 1, no. 01, pp. 26–43, 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.24127/att.v1i01.333.

N. S. L. Pakniany, A. Imron, and I. N. S. Degeng, “Peran Serta Masyarakat Dalam Penyelenggaraan Pendidikan,” J. Pendidik. Teor. Penelitian, dan Pengemb., vol. 5, no. 3, p. 271, 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.17977/jptpp.v5i3.13225.

L. Adedeji, “Islam, Education and Development: The Nigeria Experience,” Br. J. Arts Soc. Sci., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 273–282, 2012.

S. A. Kazeem and K. . Balogun, “Problems Facing Islamic Education: Evidence from Nigeria,” J. Educ. Soc. Res., vol. 3, no. 9, p. 165, 2013, doi: https://doi.org/10.5901/jesr.2013.v3n9p165.

V. Hiribarren, “Kanem‐Bornu Empire,” Encycl. Emp., pp. 1–6, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe014.

A. Yusuf Maigida, “Contemporary Islamic Education in Nigeria from the Rear View Mirror,” Am. J. Educ. Res., vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 329–343, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.12691/education-6-4-6.

K. A. Adeyemi, “The Trend of Arabic and Islamic Education in Nigeria: Progress and Prospects,” Open J. Mod. Linguist., vol. 06, no. 03, pp. 197–201, 2016, doi https://doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2016.63020.

A. I. Sani and C. Anwar, “Madrasa and Its Development in Nigeria,” J. Pendidik. Islam, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 205–216, 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.15575/jpi.v6i2.9750.

M. Bano, “Curricula that Respond to Local Needs : Analysing Community Support for Islamic and Quranic Schools in Northern Nigeria,” RISE Work. Pap. Ser., 2022, doi: https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-WP_2022/103.

Hamza Abubakar Hussain, “Role of Qur’anic Recitation Competition in Promoting the Study of Qur’anic Sciences in Nigeria: Reflections on Bauchi Metropolis,” Interdiscip. J. Educ., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.53449/ije.v3i1.100.

I. N. Muhammad and M. Abdullahi, “Giving Back to Tsangaya Schools: Exploring the Nexus between Tsangaya Graduates, School Environment and Intention to Endow Waqf,” SSRN Electron. J., pp. 1–9, 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3833542.

B. I. Muhammad, Y. A. Sanusi, L. M. Sanni, and C. B. Ohadugha, “Assessment Of The Almajiri ’ S Tsangaya Houses In The Urban Centres Of Northern Nigeria,” J. Incl. cities Built Environ., vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 39–48, 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.54030/2788-564X/2023/v3s5a4.

K. T. U, “Qur’anic schools in Taraba State: Grief and Grievances,” Zing J. Multi-Discip. Res. Educ., 2023.

H. H. Babajo and Z. Jamaluddin, “Teachers without Wages: The Challenges of Tsangaya School Teachers in Kano State Nigeria,” Educ. Adm. Theory Pract., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 1–15, 2022, doi: https://doi.org/10.17762/kuey.v28i02.398.

A. Yahya, “Tsangaya: The Traditional Islamic Education System in Hausaland,” J. Pendidik. Islam, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 1, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.15575/jpi.v4i1.2244.

A. Yakubu, “Pondok, Tsangaya, and Old Age Spiritual Wellbeing,” Tafkir Interdiscip. J. Islam. Educ., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 122–138, 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.31538/tijie.v2i2.44.

J. Sidi, R. N. Usman, and S. Abubakar, “Tsangaya System of Education in Contemporary Nigeria: Challenges and Way Forward (A Study Of Jigawa, Katsina, Sokoto And Zamfara States),” Int. J. Nov. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2022.

H. H. Babajo, Z. Jamaluddin, and A. Hamid, “The Challenges of Tsangaya Quranic Schools in Contemporary Societies: A Study of Kano State Nigeria,” Asian J. Multidiscip. Stud., vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 243–250, 2017.

M. Bano, M. Antoninis, and J. Ross, Islamiyya, Qur’anic and Tsangaya education institutions census in Kano State. Final draft report. Kano, Nigeria: Education Sector Support Programme, Kano University, 2011.

K. Bambale, “The need for the reform of Almajiri System to Education for the attainment of the Nigeria Vision 2020,” Farfaru J. Multi-Disciplinary Stud. (Special Conf. Ed., vol. 3, pp. 519–524, 2003.

I. Mājah and M. Yazīd. Sunan, “Sunan,” Beirut: Mu’assastu ar-Risālah, vol. 1, no. 215, p. 146, 2009.

N. Aeny, M. Sholikhah, W. I. Sari, I. Amaliyah, and A. F. Hidayatullah, “Fenomena Sains Dalam Al-Qur’an Perspektif Ian G. Barbour Dan Ismail Raji Al-Faruqi Science Phenomena in the Qur’an of Ian G. Barbour and Ismail Raji Al-Faruqi,” J. Yaqzhan, vol. 6, no. 1, 2020. https://doi.org/10.24235/jy.v6i1.5541.

Amrin, Ade Irmah Imamah, Nurrahmania, and A. Priyono, “Implementation of Professional Zakat of State Civil Apparatus in Indonesian in Islamic Law Perspective,” Profetika J. Stud. Islam, vol. 24, no. 01, pp. 22–32, 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.23917/profetika.v24i01.709.

H. Haerul, I. Iqra, B. M. A. Muhammad Hamad Al-Nil, and R. Mahmoud ELSakhawy, “The Role of the Teacher in Instilling Tauhid-Based Education in Students in the Perspective of the Qur’an,” Solo Univers. J. Islam. Educ. Multicult., vol. 1, no. 01, pp. 50–57, May 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.61455/sujiem.v1i01.35.

B. Z. Abubakar, “History of Islam in Middle Benue Region: A Case Study of Wukari Since 1848-1996.” Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Kano, Nigeria, 2000.

A. Rahim and A. Alqahoom, “Dialogue Language Style of the Qur’an ‘A Stylistic Analysis of Dialogues on the Truth of the Qur’an,’” Solo Int. Collab. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit., vol. 1, no. 01, pp. 35–46, Feb. 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.61455/sicopus.v1i01.29.

A. D. Amry, F. Safitri, A. D. Aulia, K. N. Misriyah, D. Nurrokhim, and R. Hidayat, “Factors Affecting the Number of Tourist Arrivals as Well as Unemployment and Poverty on Jambi’s Economic Growth,” Solo Int. Collab. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit., vol. 1, no. 01, pp. 62–71, Jun. 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.61455/sicopus.v1i01.38.

M. R. Sofa Izurrohman, M. Zakki Azani, and H. Salim, “The Concept of Prophetic Education According to Imam Tirmidzi in the Book of Syamail Muhammadiyah,” Solo Int. Collab. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit., vol. 1, no. 01, pp. 52–61, Mar. 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.61455/sicopus.v1i01.33.

U. Anzar, Islamic Education A Brief History of Madrassas With Comments on Curricula and Current Pedagogical Practices By, no. March. Paper for the University of Vermont, Environmental Programme, 2003.

R. Muhammad, A. Yusuf, and M. B. Bello, “Teachers and Parents’ Assessment of the Inclusive Education of the Almajiri and Education for All in Nigeria,” J. Resour. Distinct., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2013.

H. Babajo, “Socio-economic Menace of Almajiri Syndrome: The way out,” J. Relig. Educ. Lang. Gen. Stud. (JORELGS, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 39–45, 2008.

H. Hoechner, Search for Knowledge and Recognition. Nigeria: IFRA-Nigeria, 2018. doi: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.ifra.1425.

I. Balogun, The Life and Works of ʻUthmān Dan Fodio: The Muslim Reformer of West Africa. Africa: Islamic Publications Bureau, 1975.

D. Sartono, I. Najmi, S. Amin, and M. Bensar, “Silver as Nishab Zakat to Improve Community Welfare in the Modern Era,” Demak Univers. J. Islam Sharia, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 83–91, 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.61455/deujis.v1i02.24 Silver.

T. A.-M. Yahya Muhammad Thaib, Rania Mahmoud ELSakhawy, Muthoifin, “Marriages of More Than Four and its Impacts on Community Perspective of Islamic Law and Indonesian Law,” Demak Univers. J. Islam Sharia, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 67–82, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/deujis.v1i02.8.

F. N. Setyawan, “Analysis of the Basics of Fatwa Gold Credit DSN-MUI Perspective of Qaidah Ushul Fiqh,” Demak Univers. J. Islam Sharia, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 166–178, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/deujis.v1i03.47.

J. H. Srifyan, A. Aquil, and M. A. Zaim, “Women's Career Islamic Family Law Perspectives,” Demak Univers. J. Islam Sharia, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 154–165, 2023.

M. G. I. E. Irham Maulana, Nourelhuda S. B. Elmanaya and N. Ubed Abdilah Syarif, “Application of Hadith on Accounts Receivable and Its Implementation in Sharia Bank Guarantees,” Demak Univers. J. Islam Sharia, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 121–130, 2023.

M. Jungudo and J. Ani, “Justice and Human Dignity in Africa: A Collection of Essays in Honor of Professor Austin Chukwu,” in Oxford, African Books Collective, 2014.

I. Dahiru Idriss, M. R. Mohd Nor, A. A. Muhammad, and A. I. Barde, “A Study on the Historical Development of Tsangaya System of Islamic Education in Nigeria: A Case Study of Yobe State,” Umr. - Int. J. Islam. Civilizational Stud., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 59–71, 2022, doi: https://doi.org/10.11113/umran2022.9n2.553.

I. D. Idriss and N. H. Hamzah, “Tsangaya System of Education and its Positive Effects on Almajiri and Society in Potiskum, Yobe State Nigeria,” J. Al-Tamaddun, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 89–97, 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.22452/JAT.vol16no2.7.

R. O. F. Odumosu, S. O. O. Et Al N. I. O. S. A. E. R. (Niser), And N. Ibadan, “Manifestations of the Almajirai in Nigeria: Causes and Consequences,” in Nigerian Institute of Social and Economic Research (NISER), 2013, pp. 119–128.

S. D. U. Ayuba, “Begging among Almajiri Qur’anic boarding school children of Almajici system of education in Sokoto metropolis,” Department of Education, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, 2009.

A. U. Adamu, “Islamic Education in African Countries: The Evolution of Non-formal Al-muhajirun Education in Northern Nigeria,” in Islamic Education in African Countries, Istanbul, Republic of Turkey, 2014, pp. 1–18.

B. L. Mashema and G. S. Kawu, “The Integration Of Traditional Islamic Education Schools With The Western Education Schools Model: A Case Study Of Azare Tsangaya Model Boarding Primary School,” Int. J. Innov. Res. Adv. Stud., vol. 4, no. 7, 2017.

T. Usman, “Qur’anic Schools in Northern Nigeria: Past Glory and Prevailing Challenges,” Dirasat Tarb., vol. 7, 2018.

T. Sanyoto, N. Fadli, R. Irfan Rosyadi, and M, “Implementation of Tawhid-Based Integral Education to Improve and Strengthen Hidayatullah Basic Education,” Solo Univers. J. Islam. Educ. Multicult., vol. 1, no. 01, pp. 30–41, Feb. 2023, doi: https://doi.org/10.61455/sujiem.v1i01.31.

A. Endartiningsih, S. Narimo, and M. Ali, “Implementation of Discipline Character and Student Responsibilities Through Hizbul Wathon Extra Curricular,” Solo Univers. J. Islam. Educ. Multicult., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 39–45, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/sujiem.v1i01.32.

A. Sholikhah, “Statistik Deskriptif Dalam Penelitian Kualitatif,” Komunika J. Dakwah dan Komun., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 342–362, 1970, doi: https://doi.org/10.24090/komunika.v10i2.953.

M. Ali, “Teknik Analisis Kualitatif,” Makal. Tek. Anal. II, pp. 1–7, 2006.

S. W. Purwanza dkk., Metodologi Penelitian Kuantitatif, Kualitatif dan Kombinasi, no. March. 2022.

R. Fatha Pringgar and B. Sujatmiko, “Penelitian Kepustakaan (Library Research) Modul Pembelajaran Berbasis Augmented Reality pada Pembelajaran Siswa,” J. IT-EDU, vol. 05, no. 01, pp. 317–329, 2020.

K. Imanina, “Penggunaan Metode Kualitatif dengan Pendekatan Deskriptif Analitis dalam PAUD,” J. AUDI J. Ilm. Kaji. Ilmu Anak dan Media Inf. Paud, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 45–48, 2020. https://doi.org/10.31932/jpaud.v1i2.387.

M. B. Yunusa, Understanding the Almajiri Muslin Child and Youth Education in Nigeria. Zaria: Tamaza Publishing Company Ltd, 2013.

I. Z. Misbahu, A Study of the Students of Almajiri System of Education in Gombe Metropolis. kano: Masters’ dissertation. Kano, Bayero University, 2015.

Submitted

Accepted

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2024 Tijjani Usman Karofi

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.