RELIGIOUS HARMONY INDEX IN SPECIAL REGION OF YOGYAKARTA

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.23917/profetika.v24i02.1900Keywords:

harmony index, tolerance, religious tolerance, plurality, equalityAbstract

The existence of the Special Region of Yogyakarta as a city of students, culture, and tourism holds diversity both ethnically, culturally, and religiously; therefore, the Special Region of Yogyakarta is called the city of tolerance. The plurality of the Special Region of Yogyakarta may give rise to conflicts and divisions, including inter-religious conflicts if they are not appropriately managed. One of the successes of developing religious harmony can be assessed by looking at the most basic indicators of harmony at the national and regional levels. This study aims to measure inter-religious harmony in the Special Region of Yogyakarta. Variables that become measuring instruments have three dimensions: tolerance, dimensions, and dimensions of cooperation. The study used quantitative methods with a total sample of 400 respondents spread across Yogyakarta City, Bantul Regency, Kulon Progo Regency, and Gunung Kidul Regency. The research findings show that the index of inter-religious harmony in the Special Region of Yogyakarta is 78.90, or in the high level of religious harmony category. For this reason, maintenance must continue improving to achieve a harmonious, harmonious, and harmonious religious life. Although, in general, it is in a high category, there are still sub-dimensions that need special attention, namely caring for the construction of other places of worship and being president or regional head regardless of religion.

Deden Istiawan1*, Arif Gunawan Santoso2, Rosidin3, Ika Safitri Windiarti4

1Institut Teknologi Statistika dan Bisnis Muhammadiyah Semarang, Indonesia

2Balai Penelitian dan Pengembangan Agama Semarang, Indonesia

3Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional, Indonesia

4Universiti Muhammadiyah Malaysia, Malaysia

INTRODUCTION

Diversity is the reality of the life of the Indonesian people, whether ethnically, linguistically, culturally, or religiously . On the one hand, religious, ethnic, and cultural pluralism has the potential to knit differences into a joint force in defending the nation . However, on the other hand, it triggers the birth of acts of intolerance due to the attitude of religious adherents who are exclusive and feel more dominant than others. Adherents of other religions . as an example of the conflict between Muslims and Christians in Maluku in this reform era resurfaced. Seeing the condition of Indonesia with a variety of cultures and religions requires the community to uphold the values of tolerance and harmony among others to avoid conflicts between religious communities in society .

Religious harmony is one of the main pillars in maintaining the unity and integrity of the nation and the unity of the Republic of Indonesia . Harmony between religious communities can also be interpreted as a harmonious and dynamic social condition when all religious groups can live together without reducing their respective fundamental rights to carry out their religious obligations . Religious harmony that is not well established will result in various national development programs going to a dead end due to the absence of good cooperation between the government and the community . At this level, religious harmony must be optimized by all elements of the nation who are aware of the importance of building a harmonious character and culture .

Religious harmony is part of the pillars of development, which significantly influences success . The 2020-2024 National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) regarding religious development policies is implemented, one of which is through efforts to increase religious harmony. This mandate is in line with the strategic plan of the Ministry of Religion, namely strengthening religious harmony and harmony. Thus, the success of development in religion can be seen from inter-religious harmony . The religious harmony index is the main instrument used as a measurement tool for the achievement of harmony programs. The index of religious harmony was formed based on three main dimensions, tolerance, equality, and cooperation, based on the Joint Regulations of the Minister of Religion and the Minister of Home Affairs Number 9 of 2006 and Number 8 of 2006. The dimension of tolerance represents mutual acceptance and respect for differences. Equality reflects the desire to protect each other and give equal rights and opportunities by not prioritizing superiority .

Therefore, to increase religious harmony, the orientation is not only on tolerance alone because tolerance is only an initial requirement. For religious harmony to grow stronger, tolerance must be accompanied by an attitude of equality. Furthermore, the attitude of equality must be accompanied by concrete actions in working together in a pluralistic society. With sincere cooperation, a strong trust is built among the nation's children with a common understanding that they can live side by side in peace, calm, mutual advancement, and strengthening, not hurt and get rid of each other. So religious harmony will be formed in a society depending on tolerance, cooperation, mutual respect, mutual trust, and the ability to resolve a conflict in a community .

The existence of the Special Region of Yogyakarta (DIY) as a city of students, culture, and tourism holds various privileges both ethnically, culturally, and religiously. Therefore, DIY Province is called the city of tolerance . In addition, DIY Province is a miniature of Indonesia due to its high diversity. One of the drivers of this movement is the DIY Province as a student city. Good educational facilities and quality make people not hesitate to study in the Special Region of Yogyakarta Province for an excellent quality of life. This arrival adds to the plurality in the DIY Province . However, on the other hand, the condition of a pluralistic society often creates social friction due to the different perspectives and beliefs held by each community member. This social friction usually leads to social conflict, both horizontally and vertically. Therefore, it is necessary to have the awareness and skills of the local government and all elements of society in dealing with and managing conflict .

In several traditional historiographies, it is explained that religious harmony has been going on for several centuries ago. The emergence of Islam amid the previous religion (Hindu-Buddhism) received a positive response from the local community and authorities. Tolerance was so highly respected at that time. Empirical experience managing religious harmony is important for today's religious life. Religious harmony is influenced by educational factors, government role, and local wisdom. A person's education will affect the perspective in seeing the reality around him. Education here is not only formal but non-formal. Government as an institution different from religion needs to be present amidst religious diversity because the two cannot be separated. Meanwhile, due to the collective experience of community groups, local wisdom has great potential to encourage religious harmony.

The development of harmony varies greatly in each region, where several aspects of harmony in certain areas become a concern and have been successfully realized or have become obstacles in promoting harmony. Therefore, it is necessary to look at the success of building religious harmony based on national achievements. Related to the index of inter-religious harmony, several previous studies with various perspectives and approaches are relevant to this research. First, research conducted by . measures the level of tolerance in East Lombok Regency using the dimensions of perception, attitude, cooperation, government attitude, and people's expectations of the government. The study results show that the index of inter-religious tolerance is included in the high index category. Specifically, the dimensions of attitude and cooperation are categorized as sufficient.

The dimensions of perception, government attitudes and expectations are in the high category. Research on the tolerance index in East Lombok Regency was also carried out by . In this study, it was stated that the reality of tolerance as a social fact would not be sufficient if it were photographed only from one side, which was unable to reveal the meaning behind the fact because tolerance has an emic but also has an ethical dimension. The results of research conducted by . reveal a more comprehensive understanding of tolerance as a dynamic social reality influenced by the times and social change. Second, the research was conducted by . by measuring inter-religious tolerance in the city of Bandung. Using a quantitative method, measuring the value index of tolerance through three main dimensions: perception, attitude and cooperation between religions. The study results show that the Inter-religious Tolerance Index in the city of Bandung is in the high category, which indicates that the social interaction between religious communities in the city of Bandung has been going well and is within the limits of reasonable social distance.

The research approach to measuring religious harmony only sometimes uses a quantitative approach. Research conducted . with multicultural policies in knitting religious tolerance in Tanjung Balai. The results of the study state that the multicultural harmony policy has become a national policy that has been carried out for a long time. Even though the government has carried out various policies through various religious dialogues on an ongoing basis, the potential for conflict always exists in society. In the Tanjung Balai case, the social media factor which contributed to spreading fake news and hate speech became an important part of triggering mass anger. Therefore, it is necessary to continuously strengthen dialogue between religious leaders, policies for conveying da'wah messages that are committed to harmony, to policies through education to strengthen the spirit of nationalism. Other research was also carried out . utilizing Michael Foucault's power relations theory. This research tries to reveal the power relations of religious leaders in maintaining religious tolerance, which has implications for creating community harmony. The research results show that Islamic religious leaders have a role in maintaining tolerance because they have hierarchical power and dependence so that society can accept this role. This role is realized by providing understanding according to the teachings of Islam to the public through tussah or lectures, providing input on certain situations that are routine or incidental, and preserving religious and social activities.

The success of developing religious harmony can be assessed by looking at the most basic indicators of harmony at the national and regional levels so that the development of religious harmony varies significantly from one region to another. The condition and potential of inter-religious harmony in society's dynamics of social, cultural, and religious life can be measured through a research study to find a model of inter-religious harmony. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a research study on the social system in society that can contribute to the realization of inter-religious harmony. Seeing the condition of the DIY Province, which has a multicultural society, it is necessary to conduct a research study on the Religious Harmony Index. The purpose of this study was to determine the level of religious harmony and obtain information on mapping the strength and vulnerability of inter-religious relations in DIY Province. This research can be used by policymakers or other relevant agencies in anticipating the emergence of conflicts. The results of this research can also be used as evaluation material to improve the quality of religious harmony in the future.

METHODOLOGY

Measurement of the achievement of religious harmony programs has been carried out a lot, but not all of them can be used as a measure because they are carried out based on different objectives, techniques and standards. Therefore, the Ministry of Religion as a government agency tasked with administering government in the field of religion needs to establish a standard measure for compiling a religious harmony index that is comprehensively compiled with national standards to be used periodically .

The harmony index formed in this study is based on the Joint Regulations of the Minister of Religion and the Minister of Home Affairs Number 9 of 2006 and Number 8 of 2006, there are three major indicators: tolerance, equality, and cooperation. The tolerance indicator represents the dimensions of mutual acceptance and respect for differences. Equality reflects the desire to protect each other and to give equal rights and opportunities without prioritizing superiority. The results of this research are essential to disseminate so that all parties, especially local governments, especially in DIY Province, can serve as reference materials and preferences as a basis for compiling programs and formulating policies that are friendly to the plurality of society, proportional and fair to all entities so that they can take anticipatory actions, on potential hidden conflicts caused or labelled as religious and their derivatives before acts of violence by one community group against another .

The approach used in this research is survey research. Survey research collects information about the characteristics, actions, and opinions of a representative group of respondents from the population. The population of this survey is Indonesian citizens aged 17 years and over or married in the Special Region of Yogyakarta Province. There are four regencies/cities selected as survey locations, namely the City of Yogyakarta, Bantul Regency, Gunung Kidul Regency, and Kulon Progo Regency. The number of samples taken in each area was 100 respondents, so the total sample for this survey was 400.

The sample is determined using a tiered random sampling technique (multistage clustered random sampling). Furthermore, in each regency or city, ten villages were randomly selected. Then, ten heads of families were selected in each village. In each household, using the Kish grid method, one male respondent or one female respondent was selected. By taking this number of sample locations, it is hoped that the survey will be able to represent the answers (generalizations) of the attitudes of all religious communities regarding their relationship with followers of other religions .

This survey study aims to measure the level of inter-religious harmony in the DIY Province. Each dimension is measured using a Likert scale. At the point of the lowest scale, it is given a score of one, and at the highest point of the scale, it is given a score of four. Question items to measure the index of religious harmony in the DIY Province can be seen in Table 1. The dimensions for measuring the index of religious harmony are based on a survey of the religious harmony index conducted by the Center for Research and Development of Community Guidance and Religious Services .

Table 1. Dimensions of Religious Harmony Index

To interpret the value or level of religious harmony, a common value is prepared with a score range of 0-100. Because the answers to each question vary between 1-4, then in setting the expected value or level. The answer of respondent one will be given a score of 0, the answer of respondent two will be given a score of 25, the answering respondent three will be given a score of 75, and the answering respondent four will be given a score of 100. In contrast, respondents who stated that they did not know or did not answer would be given a score of 50. The religion obtained is categorized as follows in Table 2.

Table 2. Category Index of Religious Harmoy

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The discussion of inter-religious harmony based on the maturity of attitudes in society will, of course, always be related to the situation and physical condition of the community concerned. The conditions of rural, urban, and mountainous communities certainly have different specifications, which in the end, can have implications for the harmony created in an area .

The Department of Population and Civil Registration of the Special Region of Yogyakarta noted that the total population of Yogyakarta was 3.68 million as of June 30, 2021. Of this number, 3.41 million people (92.87%) were Muslims. 165.68 thousand (4.51%) of Yogyakarta's population embraced Catholicism. 89.54 thousand (2.44%) residents in the Student City are Christians. The population of Yogyakarta, which is Hindus, is 3.42 thousand (0.09%). A total of 3.09 thousand people (0.08%) of Yogyakarta's population are Buddhists. Then, 76 people (0.00%) of the population in the province embrace the Confucian religion. Meanwhile, as many as 363 people (0.01%) of Yogyakarta's population adhere to the belief system .

The description of the research data aims to determine the general trend of the characteristics of respondents and samples in each research variable. Characteristics of respondents seen from Religion and Marital Status. The number of respondents in this study was 400, spread over four regencies/cities, namely Yogyakarta City, Bantul Regency, Gunung Kidul Regency, and Kulon Progo Regency, with 100 respondents each.

Based on Table 3, the majority of respondents in the Special Region of Yogyakarta embraced Islam at 92%, followed by Catholic respondents at 4.5% and Christian respondents at 3.5%. The data follows the condition of the population of the Special Region of Yogyakarta based on religion in the Department of Population and Civil Registration. Based on Table 4, the number of respondents in the Special Region of Yogyakarta, the majority of their marital status is already married, 80.08%. The number of respondents who are not married is 8.3%. Respondents with widower or widow marital status were 4.75%.

Table 3. Number of Respondesnts Based on Religion

Table 4. Number of Respondents Based on Marital Status

Various efforts have been made to maintain the nation's integrity, such as requiring general education for students in Indonesia from elementary school to the high school level, even in college. This is solely an essential support for Indonesian students' abilities when directly involved in the community. The respondent's profile in terms of the latest education is presented in Table 5; the majority of respondents having the last education graduated from high school 39.50%, this shows that respondents in the Special Region of Yogyakarta have undergone nine years of compulsory education set by the government.

Table 5. Number of Respondents Based on Last Education

Education for the younger generation, both theoretical education and character education at this time, needs to be instilled as early and as good as possible to protect the younger generation from the threats of various harmful effects of globalization because the younger generation is exposed to bad things, such as intolerance, promiscuity, radicalism and other destructive effects .

Dimension of Tolerance

Tolerance is an attitude or character of tolerance, i.e., respecting and allowing an opinion, opinion, view, belief, or other that differs from one's stance . Mutual respect can also improve inter-religious relations in community life . Respecting the existence of diversity can also contribute to political and national stability. In addition, tolerance has also been shown to have economic consequences. The more tolerant a place is, the more likely it is to create a more dynamic economy . Tolerance is the basis for developing an inclusive society and democratic governance, and tolerance is included in the global sustainable development goals .

Table 6. Indicator of Tolerance Dimension

Note: Strongly Objection (SO), Objection (O), No Objection (NO), Strongly No Objection (SNO), Don't Know/No Answer (DK/NA)

Based on Table 6, 70.50% of the people in the Special Region of Yogyakarta do not mind living next door to adherents of other religions, and 26.50% do not mind living next door to followers of other religions. Respondents who expressed objections and strongly objected to living next door to adherents of other religions were 1.3%. Most of the people in the Special Region of Yogyakarta have no problem with neighbours people of different religions. In social relations, they never discriminate against someone based on their religion.

Local governments have greater authority over national policies regarding establishing places of worship. The role of local governments in granting permits for the establishment of places of worship is very decisive . Table 6 shows the community's attitude regarding the construction of places of worship for adherents of other religions that have received permission from the local government. In Table 6, 75.30% of respondents stated that they did not mind, and 19.30% strongly did not mind if there were adherents of other religions building places of worship. Meanwhile, 5.10% of respondents expressed objections and strongly objected when there were adherents of other religions building a place of worship. From these data, although the attitude of the majority of the community is positive towards religious diversity when it is associated with the construction of places of worship, there are still people who perceive it as not something that should be done .

Table 6 shows the same thing 76.50% of the people do not mind when there are adherents of other religions doing religious celebrations, and 19% of respondents say they do not mind respondents who expressed objections and strongly objected to 3.3%. Table 6 also shows tolerance when children play with adherents of other religions; 74.25% of respondents said they did not mind, and 21.50% strongly did not mind when they played with other religions. 1.75% of respondents in the Special Region of Yogyakarta expressed objections.

The four questions in the tolerance dimension show that the tolerance level between religious communities in the Special Region of Yogyakarta is still excellent. Tolerance in society is not limited to coexistence with adherents of other religions but also matters of worship. This shows that to build social relations between existing religious groups, it is significant to be called harmonious. The number who do not mind living next door to followers of other religions, do not mind if there are adherents of other religions build places of worship, do not mind when there are adherents of other religions doing religious celebrations, and do not mind when children play with adherents of other religions more than those who object or strongly objected .

Dimension of Equality

The concept of equality is interpreted, among other things, as a view and attitude to life assuming that all people are equal in terms and obligations. The right to carry out religious worship and obligations to state life and to socialize with adherents of other religions. Equality among religious people is also crucial in measuring harmony between religious communities. The concept of equality is interpreted, among other things, as a view and attitude to life assuming that all people are equal in terms and obligations. Religious pluralism is the equality of religions before the law without distinction of social status, ethnicity, skin colour, mother tongue, and religious belief, meaning that all religions have the same position before the law, not based on the majority or minority religion .

One of the fundamental aspects of religion is the right to broadcast religious teachings for both individuals and groups, which the state must fully guarantee . Religious harmony in the Special Region of Yogyakarta in terms of equality can be seen in Table 7 on the equality of rights to broadcast religious teachings. As many as 61.80% of respondents agreed, and respondents who strongly agreed, 35%, that every religious adherent was given the same right to broadcast their religious teachings following applicable laws and regulations. 3.10% of respondents stated they disagree and strongly disagree. The right to broadcast religion is part of the acceptance of equality; the value is categorically high but contributes to correcting the value of religious harmony.

Article 27, paragraph (1) of the 1945 Constitution affirms that all citizens are equal before the law. Equality before the law means that law enforcement officials and the government must treat every citizen fairly. Table 7 shows that 58% of respondents agree, and respondents strongly agree 40% that every citizen is equal before the law regardless of religion. Equality here requires equal treatment, which in the same situation must be treated equally. Article 28D paragraph (1) states: "Everyone has the right to recognition, guarantee, protection, and fair legal certainty and equal treatment before the law."

Table 7. Indicator of Equality Dimension

Note: Strongly Disagree (SD), Disagree (D), Agree (A), Strongly Agree (SA), Don't Know/No Answer (DK/NA)

Bureaucratic reform has become necessary to improve the public service delivery system to promote public welfare as mandated by the Constitution . Table 7 shows people's attitudes about equality; every citizen has the right to get the same public services regardless of religion; 55.75% of respondents agree, and 41% strongly agree.

Table 7 shows that every citizen has the right to get a decent job regardless of religion; in this question, 52.50% of respondents agreed, and 44.50% strongly agreed. Article 27, paragraph (2) of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia states, "Every citizen has the right to work and a decent living for humanity." This verse acknowledges and guarantees that everyone gets a job regardless of their religion.

Table 7 shows that every Indonesian citizen, regardless of religion, has the right to become a regional head (Governor or Mayor or Bupati or Village Head), 64.30% of respondents agree, and 24.50% strongly agree. Meanwhile, the respondents who disagreed and strongly disagreed were 10.16%.

Table 7 shows the equality of Indonesian citizens; regardless of religion, they have the right to be President of the Republic of Indonesia, 64.30% of respondents agree, and 24.50% of respondents strongly agree. At the same time, 15.10% of respondents disagree and strongly disagree. The rights of citizens to become president and vice president are regulated in Article 6, paragraph 1 of the 1945 Constitution. Every Indonesian citizen has the right to become president and vice president, whose implementation is further regulated in law.

Table 7 shows the equality of every student entitled to receive religious education in schools with the religion he adheres to; 55% of respondents agree, and 43.30% strongly agree. One of the children's rights is to receive religious teachings according to their beliefs. The regulations have regulated this to protect children's right to obtain religious education in their lives. In Law No. 23 of 2002 concerning Child Protection, Article 43 states that the protection of children's rights in embracing their religion includes coaching, mentoring, and practising religious teachings for children. Education is a means to provide equality for all students regardless of their identity or background, to develop themselves, and to defend their legal rights in any case .

Dimension of Cooperation

Harmony must give birth to cooperation to achieve common goals so that religious harmony is dynamic and not theoretical but must reflect the togetherness of religious people as a community or society . Cooperation between religious communities is essential because we are always commanded to live alongside people of other religions. Religious cooperation is the relationship between religious communities based on tolerance, mutual understanding, mutual respect, and mutual respect in the practice of equality of religious teachings and cooperation in the life of society and the state. Cooperation acts occupy the highest variable of harmony because cooperation can be realized when tolerance and equality are in good condition.

Table 8. Indicator of Equality Dimension

Note: Very Unwilling (VU), Unwilling (U), Willing (W), Very Willing (VW), Don't Know/No Answer (DK/NA)

Based on Table 8, of respondents in the Special Region of Yogyakarta, 76% stated that they were willing to visit the houses of adherents of other religions or to be visited by adherents of other religions 19.80% of respondents stated that they were very willing. As many as 4% of respondents are unwilling and very unwilling to visit the homes of adherents of other religions. The same thing is also shown in Table 8, namely participating in environmental activities involving followers of other religions, 71% of respondents are willing, and 24.80% are very willing to participate in environmental activities, such as independence celebrations, community service and so on.

The solidarity of people of different religions in the Special Region of Yogyakarta is shown by helping neighbours who are experiencing difficulties or disasters regardless of their religious status as a form of concern for others. This is shown in Table 8; 69.3% of respondents said they were willing, and 26.80% said they were very willing to help friends or neighbours who were adherents of other religions who had difficulties or calamities. This sense of solidarity grows because of the awareness of social life because they are aware and always need the help of others. Based on Table 8, 77% of respondents said they were willing, and 16% said they were very willing to be involved in a business managed with friends or friends of different religions. This statement also does not contradict the respondents' answers; 78% stated they were willing, and 18% said they were very willing, as shown in Table 8 regarding buying and selling (transactions) with neighbours or friends or relatives, or sellers of different religions. In Table 8, 78% of respondents are willing, and 16.30% of respondents stated that they are very willing to participate in community or professional organizations that involve adherents of other religions. While 5% of respondents said, they were not willing.

Analysis of the ReligiousHarmony Index

This survey research aims to measure the level of harmony between religious communities by referring to three dimensions: tolerance, equality, and cooperation. For religious harmony to grow stronger, tolerance must be accompanied by an attitude of equality. Furthermore, the attitude of equality must be accompanied by concrete actions in working together in a pluralistic society. With sincere cooperation, a strong trust is built among fellow nation's children with a common understanding that they can live side by side in peace, calm, mutual advancement, and strengthening, not hurt and get rid of each other.

Table 9. Religious Harmony Index in each Regency

Based on Table 9, the equality dimension has the highest harmony index score of 78.75%, and the lowest is the tolerance score of 72.69%. However, the dimensions of Tolerance, Equality and Cooperation fall into the high category. Overall, the community harmony index in Bantul Regency is 75.74%, which means the community harmony index is high. The inter-religious harmony that stems from the tolerant attitude of the people in Bantul Regency has been going on for a long time, showing that they can live side by side despite their different religions. Javanese customs unite them so that they work together and help each other in social activities. Then there are not a few people in the Bantul Regency who are in the same family of different religions but still have a harmonious relationship .

Based on Table 9, the equality dimension has the highest harmony index score of 83.82%, and the lowest is the tolerance dimension of 80.75%. However, the elements of Tolerance, Equality, and Cooperation are included in the category of very high community harmony. Overall, the community harmony index in Gunung Kidul Regency is 81.83%, which means the community harmony index is very high.

Good religious harmony in Gunung Kidul Regency is the role of all parties, ranging from elements of society, government, religious leaders, community leaders, youth leaders, and ethnic leaders. Mutual respect and respect between religious communities is a key and significant capital in maintaining harmony and harmony between religious communities.

Based on Table 9, the equality dimension has the highest harmony index score of 78.57%, and the lowest is the cooperation score of 77.13%. However, the dimensions of Tolerance, Equality and Cooperation fall into the high category. Overall, the community harmony index in Kulon Progo Regency is 77.63%, which means the community harmony index is high.

Based on Table 9, the tolerance dimension has the highest harmony index score of 83.06%, and the lowest is the cooperation score of 75.08%. However, the elements of Tolerance and Equality are included in the category of very high community harmony. Overall, the community harmony index in Yogyakarta City is 80.38%, which means the community harmony index is high.

Index of Religious Harmony in the Province of the Special Region of Yogyakarta

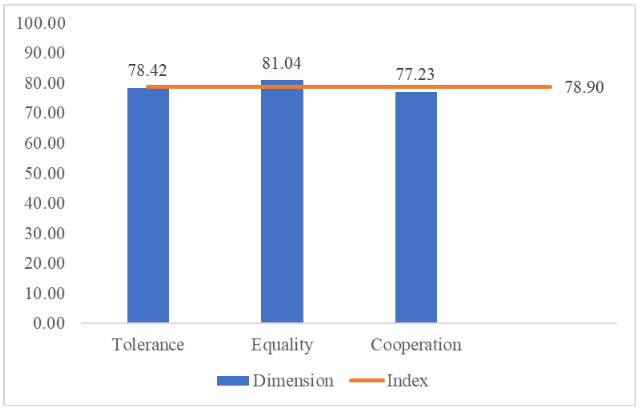

This value of religious harmony is an illustration of the achievements of the research objectives. The research aims to find out what the score of the harmony of the people is in the Province of D.I Yogyakarta. Figure 1 shows the average score of religious harmony in the Province of D.I Yogyakarta. Based on Figure 1 the Index for Religious Harmony in the Province of D.I Yogyakarta of 78.90% is included in the category of High inter-religious harmony. While the indicator scores for Tolerance, Equality and Cooperation are 78.42%, 81.04% and 77.23%.

Figure 1. Index of Religious Harmony in the Province of the Special Region of Yogyakarta

Analysis of Correlation Between Dimensions of Religious Harmony

Correlation analysis is a term commonly used to describe whether there is a relationship between one thing and another. Correlation analysis is a method to determine whether there is a linear relationship between variables. If there is a relationship, the changes in one variable will result in changes in the other variables. A correlation between two variables is not always linear, such as the addition of the value of the Y variable if the X variable increases, this kind of correlation is called a positive correlation. Sometimes it is found that there is a relationship where if one variable value increases, the other variable decreases; such a relationship is called a negative correlation.

Table 10. Correlation Coefficient Between Dimensions of Religious Harmony

Based on Table 10, it can be seen that the correlation coefficient value between the dimensions of religious harmony and the index value of religious harmony. The value of the correlation coefficient of the tolerance dimension is 0.70, which means that the relationship between the tolerance dimension and the harmony index is strong. Correlation coefficient value between the dimensions of religious harmony and the index value of religious harmony. The value of the correlation coefficient of the tolerance dimension is 0.66, which means that the relationship between the tolerance dimension and the KUB index is strong. The correlation coefficient value of the equality dimension is 0.73, which means that the relationship between the equality dimension and the KUB index is strong. The correlation coefficient value of the cooperation dimension is 0.68, which means that the relationship between the cooperation dimension and the KUB index is strong. To see in more detail the indicators that make up the index of religious harmony, see Table 11, which is an indicator that makes up the dimension of tolerance. The construction of places of worship for adherents of other religions is one of the most significant indicators in the dimension of tolerance.

Table 11. Correlation Coefficient of Tolerance Dimension

Table 12. Correlation Coefficient of Equality Dimension

Furthermore, the indicators on the dimension of equality can be seen in Table 12. The perspective of equality cannot be separated from a political perspective. The acceptance of regional heads of other religions is quite significant in contrast to national leaders. The dynamics of regional leadership without really questioning religion are quite interesting. Religious background does not seem to be the primary benchmark; the evidence is that people accept these differences.

Table 13. Correlation Coefficient of Cooperation Dimension

Furthermore, the indicators for the dimensions of cooperation can be seen in Table 13. Harmony is related to life experience and willingness to cooperate with followers of other religions. Both in daily life and the relationship between professions and economic interests, it is an essential factor to see the attachment to each other. Specifically, the indicator of participating in a community or professional organization that involves other religions and a business managed with friends of different religions is lower in value than other indicators in collaboration. However, the existing numbers reflect the relationship between religious communities who are factually willing and have had a relatively high level of cooperation.

CONCLUSION

In the research, three main dimensions are used to measure the level of harmony in the Special Region of Yogyakarta: tolerance, Equality, and interfaith cooperation. The research results on tolerance perceptions score 78.42, 81.04; Equality and Inter-religious Cooperation 77.23. From the average results obtained, it can be concluded that inter-religious harmony in the Special Region of Yogyakarta is 78.90, which is already high. For this reason, maintenance must continue improving to achieve a harmonious, harmonious, and harmonious religious life. Although, in general, it is in a high category, there are still sub-dimensions that need special attention, namely from the dimension of tolerance, the community objected to the construction of places of worship of other religions. From the dimension of Equality, people in the Special Region of Yogyakarta do not agree if people of different religions and themselves become presidents of the Republic of Indonesia. From the dimension of cooperation, the community is unwilling to visit houses of worship adherents of other religions and engage in business with colleagues of different religions.

To maintain religious harmony in the Special Region of Yogyakarta, one thing that can be done is to maximize the role of FKUB in each region by making conflict maps in each region based on the results of a survey of religious harmony. Then, the Government needs to build a centralized coordination mechanism. This is done to take preventive and solution steps in handling various potentials of disharmony and social conflict in their respective contexts.

Acknowledgments

This research has been funded by Balai Penelitian dan Pengembangan Agama Semarang (BLAS). We want to thank the Head of the Semarang Religious Research and Development Center for providing the opportunity to conduct this research, as well as the survey officers and respondents who have helped distribute and fill out the research questionnaire.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper, all authors read and approved the final paper, and all authors declare no conflict of interest.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

M. A. Lubis, “Budaya dan Solidaritas Sosial dalam Kerukunan Umat Beragama di Tanah Karo,” J. Ilm. Social. Agama dan Perubahan Sos., vol. 11, no. 02, pp. 239–258, 2017.

A. J. Afandi, “Best Practice Pembelajaran Toleransi (Implementasi Kajian Tematik Hadith Al-Adyan Bagi Kerukunan Umat Beragama),” NUANSA J. Penelit. Ilmu Sos. dan Keagamaan Islam, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 65, 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.19105/nuansa.v16i1.2365.

D. O. Daeli and S. E. Zaluchu, “Analisis Fenomenologi Deskriptif terhadap Panggilan Iman Kristen untuk Kerukunan Antar Umat Beragama di Indonesia,” SUNDERMANN J. Ilm. Teol. Pendidikan, Sains, Hum. dan Kebud., vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 44–50, 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.36588/sundermann.v1i1.27.

R. Hermawati, C. Paskarina, and N. Runiawati, “Toleransi Antar Umat Beragama di Kota Bandung,” Umbara, vol. 1, no. 2, 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.24198/umbara.v1i2.10341.

D. A. Rizal and A. Kharis, “Kerukunan Dan Toleransi Antar Umat Beragama Dalam Mewujudkankesejahteraan Sosial,” Komunitas J. Pengemb. Masy. Islam, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 34–52, 2022.

N. K. Afandi, “Belajar dari Kerukunan Antar Umat Beragama di Kalimantan Timur dan Implikasinya terhadap Pendidikan Karakter,” AL-MURABBI J. Stud. Kependidikan dan Keislam., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 143–165, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.53627/jam.v4i2.3172.

T. Rambe, “Implementasi Pemikiran A. Mukti Ali terhadap Problem Hubungan Antar Umat Beragama di Indonesia,” J. Anal. Islam., vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 104–116, 2017.

S. Ibrahim, “Efektivitas Kebijakan Pelaksanaan Kerukunan Umat Beragama,” Al-Mishbah | J. Ilmu Dakwah dan Komun., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 43, 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.24239/al-mishbah.vol12.iss1.66.

A. Safithri, Kawakib, and H. A. Shiddiqi, “Implementasi Nilai-Nilai Moderasi dan Toleransi Antar Umat Beragama dalam Menciptakan Kerukunan Masyarakat di Kota Pontianak Kalimantan Barat,” Al Fuadiy, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 13–26, 2022. https://doi.org/10.55606/af.v4i1.7

R. Sinulingga, “Fundamentalisme Agama dengan Kajian Biblis tentang Kerukunan Risnawaty Sinulingga,” J. Amanat Agung, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 227–246, 2014.

M. K. Fatih, “Dialog Dan Kerukunan Umat Beragama Di Indonesia,” Reli. J. Stud. Agama-Agama, vol. 13, no. 01, p. 38, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.14421/rejusta.2017.1301-03.

A. Ismail, “Refleksi Pola Kerukunan Umat Beragama (Fenomena Keagamaan di Jawa Tengah, Bali, dan Kalimantan Barat),” Analisa, vol. XVII, no. 2, pp. 175–186, 2010. https://doi.org/10.18784/analisa.v17i2.36

M. Hasibuan, “Aktualisasi Pancasila dan Kerukunan Umat Beragama di Kota Bengkulu,” J. Pancasila dan Kewarganegaraan, vol. 1, no. 1, 2021.

M. Yunus, Ngimadudin, Y. Arikarani, and I. Umar, “Indeks Kerukunan Umat Beragama Lubuklinggau Tahun 2019,” Khabar (Jurnal Komun. Penyiaran Islam., vol. 1, no. 1, 2019.

L. K. Nuriyanto, “Modal Sosial Dalam Membingkai Kerukunan Umat Beragama Di Surakarta,” Al-Qalam, vol. 24, no. 2, p. 271, 2018. https://doi.org/10.31969/alq.v24i2.477

Makhrus, “Peran Forum Pemuda Kerukunan Umat Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta Dalam Memperkuat Paradigma Inklusif Kaum Muda,” Wahana Akad., vol. 4, no. April, 2017. https://doi.org/10.21580/wa.v4i1.1482

A. Priyantaka and Suharno, “Upaya Memelihara Kerukunan Umat Beragama Melalui Program Kerja Forum Kerukunan Umat Beragama (FKUB) Kota Yogyakarta,” J. Pendidik. Kewaraganegaraan dan Huk., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 25–37, 2020.

A. A. Rachman, “Dinamika Kerukunan Umat Beragama Dalam Kepemimpinan Kesultanan Yogyakarta,” Akademika, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 91–92, 2014.

Sulaiman, Z. Fikri, and A. Busyairi, “Toleransi Antar Ummat Beragama Di Kabupaten Lombok Timur Tahun 2020,” J. Edukasi dan Sains, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 38–50, 2021.

A. Tohri, A. Rasyad, S. Sulaiman, and U. Rosyidah, “Indeks Toleransi Antarumat Beragama Di Kabupaten Lombok Timur,” J. Ilmu Sos. dan Hum., vol. 10, no. 3, p. 563, 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.23887/jish-undiksha.v10i3.38822.

H. Daulay, “Kebijakan Kerukunan Multikultur dalam Merajut Toleransi Umat Beragama (Studi Atas Pemolisian Kasus Azan Di Tanjung Balai Sumatera Utara),” J. Manaj. Dakwah, vol. 1, no. 2, p. 19, 2019.

A. Salim and A. Andani, “Kerukunan Umat Beragama; Relasi Kuasa Tokoh Agama dengan Masyarakat dalam Internalisasi Sikap Toleransi di Bantul, Yogyakarta,” Arfannur, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.24260/arfannur.v1i1.139.

S. Rukhayati and T. Prihatin, “Work Stress and Influencing Factors,” Solo Int. Collab. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit. SICOPUS, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 44–51, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/sicopus.v1i01.30

A. Rahim, “Dialogue Language Style of the Qur’an" A Stylistic Analysis of Dialogues on the Truth of the Qur’an",” SICOPUS; Solo Int. Collab. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit., vol. 1, no. 01, pp. 33–43, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://journal.walideminstitute.com/index.php/sicopus/article/view/29

T. Oktatianti, “Premeditated Murder in the Modern Era Comparative Study of Perspectives on Islamic Law and the Criminal Code Pembunuhan Berencana di Era Modern Studi Komparatif Perspektif Hukum Islam dan KUHP,” Solo Int. Colab. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 24–32, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/sicopus.v1i01.28

S. Al, F. Lingga, and A. Mustaqim, “History of the Development of Philosophy and Science in the Islamic Age,” Solo Int. Collab. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/sicopus.v1i01.5

D. R. Purwasari, M. Nur, and R. Maksum, “The Strategy of Islamic Education Teachers in Instilling Student Moral Values at State Vocational High School 6 Sukoharjo,” Solo Int. Collab. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 13–23, 2023.

V. B. Kusnandar, “Jumlah Penduduk Yogyakarta Menurut Agama/Kepercayaan,” 2021.

F. Averoezy, D. Agung Prasetyo, and E. Kusumastuti, “Peranan Pendidikan Agama Islam Dalam Menjaga Kerukunan Umat Beragama,” Atta’dib J. Pendidik. Agama Islam, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 14–27, 2021. https://doi.org/10.30863/attadib.v2i2.1822

H. J. Prayitno et al., “Prophetic educational values in the Indonesian language textbook: pillars of positive politeness and character education,” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 8, p. e10016, 2022, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10016.

M. R. T. L. Abdullah, M. N. Al-Amin, A. Yusoff, A. Baharuddin, F. Abdul Khir, and A. T. Talib, “Socio-Religious Harmony Index Instrument Indicators for Malaysia,” J. Al-Tamaddun, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 29–44, 2016, doi: https://doi.org/10.22452/jat.vol11no2.3.

M. I. I. Zulkefli, M. N. A.-A. Endut, M. R. T. L. Abdullah, and A. Baharuddin, “Towards ensuring inter-religious harmony in a multi-religious society of Perak,” SHS Web Conf., vol. 53, p. 04006, Oct. 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20185304006.

N. Berggren and T. Nilsson, “Tolerance in the United States: Does economic freedom transform racial, religious, political and sexual attitudes?,” Eur. J. Polit. Econ., vol. 45, pp. 53–70, 2016, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.06.001.

R. Ardi, D. H. Tobing, G. N. Agustina, A. F. Iswahyudi, and D. Budiarti, “Religious schema and tolerance towards alienated groups in Indonesia,” Heliyon, vol. 7, no. 7, p. e07603, 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07603.

C. Pamungkas, “Toleransi Beragama Dalam Praktik Sosial: Studi Kasus Hubungan Mayoritas dan Minoritas Agama di Kabupaten Buleleng,” Epistemé J. Pengemb. Ilmu Keislam., vol. 9, no. 2, 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.21274/epis.2014.9.2.285-316.

A. D. Amry, F. Safitri, A. D. Aulia, K. N. Misriyah, D. Nurrokhim, and R. Hidayat, “Factors Affecting the Number of Tourist Arrivals as Well as Unemployment and Poverty on Jambi ’ s Economic Growth,” Solo Int. Collab. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 62–71, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/sicopus.v1i01.38

M. R. S. Izurrohman, M. Z. Azani, and ..., “The Concept of Prophetic Education According to Imam Tirmidzi in the Book of Syamail Muhammadiyah,” Solo Int. Collab. Publ. Soc. Sci. Humanit., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 52–61, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://journal.walideminstitute.com/index.php/sicopus/article/view/33%0Ahttps://journal.walideminstitute.com/index.php/sicopus/article/download/33/29

S. A. Sahfutra, “Gagasan Pluralisme Agama Gus Dur Untuk Kesetaraan Dan Kerukunan,” Reli. J. Stud. Agama-Agama, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 89, 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.14421/rejusta.2014.1001-06.

H. L. Hakim, “Hak Kebebasan Ekspresi Beragama Dalam Dinamika Hukum Dan Politik Di Indonesia,” J. Huk. dan Perundang-undangan, vol. 1, no. 1, 2021. https://doi.org/10.21274/legacy.2021.1.1.96-111

N. S. Maryam, “Mewujudkan Good Governance Melalui Pelayanan Publik,” J. Ilmu Polit. dan Komun., vol. VI, no. 1, pp. 1–18, 2016.

K. Jayadi, A. Abduh, and M. Basri, “A meta-analysis of multicultural education paradigm in Indonesia,” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 1, p. e08828, 2022, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08828.

A. Rachmadhani, “Dimensi Etnik Dalam Kerukunan Umat Beragama Di Kota Pontianak Provinsi,” J. Penelit. Agama dan Masy., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1–21, 2018. https://doi.org/10.14421/panangkaran.2018.0201-01

Downloads

Submitted

Accepted

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Deden Istiawan, Arif Gunawan Santoso, Rosidin, Ika Safitri Windiarti

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.