BEYOND MORTGAGES: ISLAMIC LAW AND THE ETHICS OF CREDIT FINANCING FOR PUBLIC HOUSING

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.23917/profetika.v24i02.1795Keywords:

housing, taxation, affordable housing, banking marketing model, economic developmentAbstract

Having a home is essential for everyone, and the government created a program called Housing Loan (KPR) to help low-income people own a house. The Sharia State Savings Bank (BTN) is one of the banks that offer this program. This study aims to understand how KPR works at Bank BTN KCPS Pekalongan and how it aligns with Islamic law. This type of research is field research, which outlines and describes phenomena regarding the situation. In this case, the kind of research is qualitative. This research can also be considered sociological research because it is carried out directly in the field, and the data received will be evaluated inductively to make arguments for the KPR transaction system at BTN KCPS Pekalongan with Sharia principles and appropriate legislation. The study found that BTN KCPS Pekalongan uses murabahah and istishna sale and purchase contracts for KPR. Murabahah contracts are commonly used, and Istishna contracts are used for one product called KPR BTN Indent I.B. The study recommends that the bank introduce other Sharia KPR products to the public to increase awareness

Muhamad Subhi Apriantoro1, Eis Rantika Puspa2, Dandi Ibtihal Yafi3, Deast Amanda Putri4, Rozi Irfan Rosyadi5

1Faculty of Islamic Religion, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Indonesia

2Sharia Economic Law Study Program, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Indonesia

3Sharia Economic Law Study Program, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Indonesia

4Faculty of Islamic Religion, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Indonesia

5Human Resources & School of Management Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University Hyderabad, India

INTRODUCTION

Banks are institutions that save money, lend money, and make deeds payable . The role of banks has an impact on the economic development of a country . This is due to the function of the bank as an intermediary. Moreover, banks and other financial institutions play an essential role in people's lives because they can reach every community without distinction. Thus, explanations about banking and other financial institutions can be realized correctly .

Islamic banks are described in "Law Number 10 of 1998 concerning Amendments to Law Number 7 of 1992 concerning Banking". The existence of Islamic Banks, according to "U.U. No 10/1998, namely one form of bank business providing financing or carrying out other activities based on sharia principles, following the provisions stipulated by Bank Indonesia". Islamic banks apply the principle of profit sharing, namely between the bank and the depositor of funds (shahibul maal) or the debtor of funds (mudharib). Islamic banking activities are generally divided into three categories: collecting funds, distributing financing, and other Islamic banking services .

Islamic banks' most common financing product is the istishna' contract principle. Istishna' is a producer's agreement with the customer to do what is stipulated in the contract with certain conditions . Although, since the beginning, the Muslim community (Ulama) has denied this, the istishna contract is usually used to finance Islamic banks, one of which is development projects, so it is appropriate for the customer's needs to make constructions such as building houses .

Home is a basic need for all humans, besides food and drink. The function of the house is essential to function for community activities. However, some people do not have private residences. Of course, it is not easy for people with low incomes to buy a house in cash because of high house prices. The 1945 Constitution Article 28 H paragraph (1) on the right to live for everyone explains that "everyone has the right to live in physical and spiritual prosperity, to have a place to live and to get a good and healthy environment and has the right to receive health services" . January 29, 1974, the Government of Indonesia, with the "Letter of the Minister of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia No. B-49/MK/I/1974 as a forum for financing housing projects for the people. With the enactment of the letter in 1976, the first KPR (House Ownership Credit) offer in Indonesia appeared to BFinallyally, BTN was the only bank that developed the housing industry in Indonesia through KPR BTN. Number 7 - Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia (TLNRI) Number 5188, promulgated on January 12, 2011. According to Article 166 of Law Number 1 of 2011, this Law came into force , [1].

Law Number 4 of 1992 concerning housing and settlements (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia of 1992 Number 23, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 3469) was repealed and declared null and void. However, this is how the housing needs of the Indonesian people want to be achieved, so the State provides and organizes programs to achieve these goals through the Public Housing Credit program . The KPR scheme is carried out by a bank whose function is to collect funding from the community and pass it on to the community .

Over time, the Islamic community found that the mortgage system implemented by Islamic banking was not by Islamic principles. Islamic banks use the name of the contract (transaction) in Islam to carry out products in Islamic banking. However, the transaction system is similar to the conventional banking system. "From this reality, we just want to emphasize one conclusion that consumers (customers) do not make house buying and selling transactions with banks at all .

Likewise, banks do not buy houses from developers at all. This practice applies to both conventional banks and Islamic banks. Regarding mortgages made by Islamic banking, Islam does not prohibit buying and selling using the credit system. Allah Ta'ala says means it: "O you who believe, if you do not do mu'amalah in cash for a specified time, you should write it down." (Q.S. Al-Baqarah: 282). However, if the transactions carried out have violated Islamic Law, then that is what is prohibited. One of the transactions that violate Islamic Law is a transaction that contains elements of usury. Buying and selling with a credit system is very vulnerable to containing elements of usury. Riba occurs when the debtor is due in payment which is then subject to a fine, then the penalty riba or occurs in the presence of interest .

The desired research has academic and practical benefits. As for academic benefits, namely the development of the scientific theory of Islamic economics, especially the istishna contract as one of the credit products in the contract of buying and selling goods and notifying the agreed price and profit for sellers and buyers in housing management, it can also be used as a reference for parties who will carry out similar research .

Implementing the istishna contract concept in mortgage financing at BTN KCPS Pekalongan, the customer comes to the BTN KCPS Pekalongan bank to submit a house order. First, the BTN KCPS Pekalongan Bank contacts the developer to order the house according to the criteria specified by the customer, then the BTN KCPS Bank Pekalongan contacts customers to make a transaction that the place already exists. Finally, the customer must pay a down payment (D.P.) as a receipt to the BTN KCPS Pekalongan bank. Therefore, KPR with an istishna contract carried out by BTN Sharia is essential. For this reason, it carries out an Istishna contract, namely KPR BTN Indent I.B , [2]. The stages and scheme of the istishna contract are the same as the murabaha contract, the only difference being the installments. In an istishna' agreement, the customer does not need to pay off before the house is finished. However, customers are still required to pay a down payment (D.P.). Regardless of the bank's identity as a financial institution, the bank may not require a down payment (D.P.) from the client because the conditions here are only for sellers .

Therefore, if the bank requires a down payment, the bank has a debt, and a kind of sale and purchase is forbidden in Islam. In this case, the istishna contract can only be carried out by the producer, namely the developer. Based on the opinion of most scholars, the istishna contract is a particular salam contract, the conditions for which can be said to be the same as a salam contract. All prices of goods and time of delivery of goods must be determined according to the order. In the istishna contract, the seller is a producer and can request a down payment or D.P. Even though the merchant carries out the sale and purchase contract, the price cannot be made in advance and must be in cash, even though the goods have been delivered a few days later .

Based on the research results that the authors describe, the KCPS Pekalongan State Savings Bank in the KPR transaction system has two contracts: a murabahah contract and an istishna contract. The first, a review of Islamic Law on mortgages using a Murabaha contract from Bank BTN KCPS Pekalongan, says that the scheme used is a Murabaha scheme, but in the contract, what happens is the financing of the loan is returned with interest so that customers do not get services from bank BTN. Because it is the customer who has to find the developer himself, not the bank. Even though the Murabaha scheme is written, in the research conducted by bank researchers, they needed to carry out the project in the right direction. So the bank should continue to run the murabahah scheme by Islamic Law, where it is not the customer who has to find the developer himself after getting the loan financing .

Returned with interest, but the bank that had bought the house from the developer should have sold it to the customer by raising the price for the bank to get a profit or margin from the mortgage sale and purchase transaction. For an Islamic legal review of mortgages using the istishna contract, BTN Syariah KCPS Pekalongan is by Islamic Law because it is an order sale where the house has not been completed. Still, the customer orders a house with the bank by paying a down payment (D.P.) .

Even though Bank BTN KCPS Pekalongan said that the scheme used was a Murabaha scheme, in the contract, what happened was the financing of the loan was returned with interest, so customers did not get services from the bank .

BTN. Because it is the customer who has to find the developer himself, not the bank. The customer applies for financing to buy a house, not for business. What should have happened at Bank BTN KCPS Pekalongan was that the bank contacted the developer, but the place was already finished, and then the bank raised the house price to get a margin or profit for the customer , [3].

The istishna scheme is by Islamic Law because the bank is only an intermediary or representative, which is a buying and selling order that the house is not finished, but the customer orders a place with the bank by paying a down payment (D.P.). Suppose the customer does not pay off the transaction; the bank returns (D.P.). Bank BTN proposes to buy a house from the developer. Then the bank asks the customer for a commission as a service fee for finding a home .

METHODOLOGY

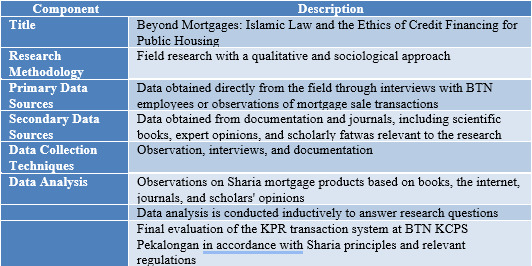

This type of research is field research, which outlines and describes phenomena regarding the situation. In this case, the kind of research is qualitative. This research can also be considered sociological research because it is carried out directly in the field . Primary Data Source Obtained directly in a personal way by the source. This method involves in-person interviews, via email, or other means of communication. Primary data is generally obtained directly personally. In this research, preliminary data was obtained directly from the field or through interview findings with one of the BTN employees or observations observing the natural occurrence of the mortgage sale transaction. Secondary Data Sources Defined data that is combined, worked on and presented by other parties such as the mass media, research findings, or reports that have been carried out. In this research, secondary data was obtained through the application of documentaries and journals, namely scientific books, expert opinions, and scholarly fatwas that match the topics in the research .

The authors apply techniques including observation, interviews, and documentation to obtain data that is used to research. Data analysis carried out by the author is to make observations based on Sharia mortgage products with information from books, the internet, and journals, as well as some opinions of scholars. After completing all research activities, the next step is to analyze the data obtained. Data analysis aims to answer research questions that have been formulated. In general, qualitative data analysis occurs during data collection. Finally, the data received will be evaluated inductively to make arguments for the KPR transaction system at BTN KCPS Pekalongan with Sharia principles and appropriate legislation .

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

An Islamic bank is defined as a bank that operates independently from interest, business, and products developed under the Qur'an and hadith. Therefore, Islamic banking operates on Islamic principles and is a type of Islamic commercial bank and Islamic people's financing bank that has a relationship between business activities, Islamic business units, Islamic banks, and the occurrence when implementing business activities .

It has the function of collecting and distributing funds from people. Islamic banking combines the city's budget as a deposit by implementing an al-wadiah contract and a form of investment that uses an al-mudharabah agreement and as a baitul maal institution. In addition, Islamic banking aims to store financial facilities through financial liaison efforts that are equivalent to Islamic provisions and Shari'a .

Home Ownership Loans (KPR) are instalments offered to customers through a management (rental) program for the price of the house provided. Banks finance mortgage loans, and KPR is included in consumer loans for personal needs (BTN, 2019). Home Ownership Credit (KPR) is a facility that banks distribute to buyers who will order a house. The following are two types of mortgages in Indonesia: subsidized and non-subsidized. Subsidized KPR, namely instalments are given to residents who have low incomes to fulfill their housing needs or to repair their previous homes. The government regulates these subsidies individually, so not all cities can get them .

Non-subsidized KPR, namely KPR, for the wider community. The bank determines the mortgage terms, and then the loan amount and interest rates follow the bank's policy (Hong Thai & Quach). Al-bay' in Arabic means exchanging. Based on the term, namely the exchange of assets based on an agreement. The concept of buying and selling according to Sharia is the exchange of goods by two or more people voluntarily, joint ownership by buying and selling. The seller has the right to get legal money, the buyer has the right to the goods the seller has received, Law secures the parties .

The pillars of buying and selling are defined as everything that must be included in buying and selling to carry out transactions. There are three pillars of buying and selling. Namely, there are organizers, sellers, and buyers, who have met the requirements. Finally, contracts or transactions exist, and goods or services are traded .

The requirements for a valid sale and purchase contract are that the seller and the buyer are people who are mature and have common sense or mumayyiz (able to distinguish between good and bad), who are seven years old. Children who are mumayyiz may buy and sell. The second requirement is self-will, not coercion by others. If forced by other people, buying and selling is not valid. For example, if a seller forces him to buy his wares with the threat of a sharp weapon or something else, the sale and purchase are not valid . This provision follows the Prophet's hadith, which says that buying and selling must be consensual.

The third requirement is that the seller and the buyer must be at least 2 (two) people, and it is not legal to buy and sell alone. The fourth requirement for goods sold must be perfect property (own property). Buying and selling are not valid if the goods being sold are not his own but belong to someone else unless there is a proper authority by giving power of attorney to him. The five conditions for the goods being sold must be clear in form and can be delivered. The sixth condition is that goods sold must be pure, according to Syara'. It is not legal to buy and sell something unlawful in substance. The seventh requirement for goods traded must be obtained lawfully. Illegal sale and purchase of goods result from robbery, theft, corruption, etc.

Apart from being called debt, the word credit is also called in conventional banking and Islamic banking. The person who lends his property to another person is said to be indebted to him. Residents use financing or credit for transactions in banking and non-cash purchases. There is not much difference between what is meant by debt and credit or financing within a group. Financing is the provision of funds by one party for another party to help the investment itself or other institutions. It can also be interpreted as spending money to help with planned investments.

Law Number 10 of 1998 states "that financing based on sharia principles is a provider of money or bills that are equivalent based on an agreement or agreement between a bank and another party that requires the party being financed to return the money or bill after a certain period in return or for results".

A trust generally submits funding. So providing financing means sharing Trust. This means there must be confidence that the shared performance can be returned to the financing provider within the agreed or predetermined time and conditions. Several financing elements include the following: There are two parties, namely the provider and recipient of financing. Trust is the lender's belief that the recipient will return the debt on time and both parties agree to the terms, agreement, or agreement between the lender and the recipient of the financing. The term is the agreed loan repayment period, risk, namely, there is a payback period that will result in the risk of not being billed for financing (non-performing loans), remuneration, namely profit on granting a loan. This service is called profit sharing or margin .

Financing has a function to develop job prospects and economic benefits of Islamic values. Therefore, this financing needs to be made available as much as possible for entrepreneurs in industry, agriculture, and trade to support the production and distribution of goods and services to complement the needs of the domestic and imported communities.

Istishna' based on fiqh is buying and selling in the form of an order or arrangement of goods with terms and criteria that have been agreed upon between the buyer (buyer) and the seller. Istishna' based on Bank Indonesia Regulations (PBI), is the sale and purchase of ordered goods or the manufacture of goods according to specific agreed terms and criteria and appropriate payments (PBI Number 7/46 article 1 point 9). Based on the Hanafi school of thought, the istishna contract is a sale and purchase contract for ordered goods. This is not an ijarah contract for work.

Therefore, if the craftsman provides products that he does not make himself, or if the goods are made before the contract occurs but are in the desired shape, the contract for these goods can be considered valid. It can be concluded that Istishna' is a sale and purchase transaction by order, where the buyer orders goods from the seller, and the payment can be made directly, in stages according to the work process, or can be paid in long-term instalments, all can be made following the agreement. The legal basis of buying and selling istishna' is the same as buying and selling greetings.

From this basis, the Hanafi school of thought suggests that the principle of buying and selling istishna' is not permissible. If allowed, the practice among the population has become a culture, and there is no gharar or cunning. Therefore, in buying and selling istishna', the buyer places the seller to give the order according to the specifications. Next, it is given by the buyer by way of early payment. The buyer and seller agree upon the specifications and price of ordered goods at the beginning of the contract. The price provisions for ordered goods cannot be changed during the contract period. The Law of bai' al-istishna' is permissible because it can alleviate and make it easier for every human being to do muamalah.

In the Istishna Funding Pillars, the perpetrator of the contract, namely the buyer (mustashni) and the seller (shani), must be able to reach puberty, have good skills, not be crazy, and not pushy. Transactions involving minors can only be carried out with the permission and supervision of a legal guardian. DSN requires sellers to deliver products on time at the agreed quality and quantity. Distributors can deliver goods earlier than the agreed time and products according to the agreement at no additional cost. The object of the contract includes goods and prices for Istishna' products and product prices, including the object of the contract for Istishna's sale and purchase transactions.

Ijab and qabul istishna' are expressions of two parties in the form of an offer from the receiver appointed by the seller and the buyer. You can cancel the contract in person, conditionally (for those who cannot speak), by action, or in writing. Trusting social customs shows the parties' satisfaction with the sellers of istishna products and the buyers of istishna products.

As for the nature of the istishna contract, it is a common (non-binding) ghairu contract, meaning before and after carrying out an order. So because of that, for the parties, there is the right of khiyar to consummate and decide on the contract and withdraw the contract before musthani' watches the product being made/ordered. Suppose the shani makes a product that mustashni has not seen. In that case, the Law of the contract is valid because there is general gharar, and the object of the contract is not the object of manufacture itself, but something like that is still in the family.

If the producer brings his creation to (the customer), then his khiyar is invalid because he is deemed to have agreed to his actions to the consumer (customer). If the buyer has seen the goods, he can have the right to pay and cancel the contract. According to Iman Abu Hanifah and Muhammad, he is entitled to khiyar because he has bought something he has not seen. However, Imam Abu Yusuf stated that if the customer sees the goods ordered, the contract becomes common (binding), and there is no right of payment if the goods meet the conditions set out in the agreement. Therefore the goods are the subject of the contract and have the same status as the salam contract. That is, they are not khiyar. So in this case it is to eliminate losses due to damage to the materials that have been made, and if they are sold to other people, they don't necessarily want to.

BTN Syariah is a Strategic Business Unit (SBU) that operates based on Islamic principles, opening its first branch in Jakarta on February 14, 2005. This SBU was formed to serve the community's interests in Sharia financial services, Islamic banking principles, the MUI fatwa on bank interest, and the results of the 2008 GMS. 2004. Starting with changes to banking regulations by the government, "Banking Law No. 7 of 1992 became Banking No. 10 In 1998, the banking world became popular with the development of Islamic banks. As a result, competition in the banking market is getting tighter. Not to mention the issuance of PBI No4/I/PBI/2002 concerning changes in the business activities of conventional commercial banks to become Islamic commercial banks, with the increasing number of UUS (Sharia Business Units). Then the management of PT BTN (persero) through the steering committee meeting of the BTN restructuring implementation team on December 12, 2013.

Management of Bank BTN prepared work plans and amendments to the articles of association to open UUS to compete in the Sharia banking market. No.29 dated October 27, 2004, by Emi Sulistyowati, SH Notary in Jakarta, which marked the formation of the sharia division based on Directors Decree No.14/DIR/DSYA/2004.

Murabahah contract is an agreement between the seller and the buyer which determines the production price, and the profit or profit is regulated by mutual agreement. The legal basis for a murabahah contract is the Fatwa of the National Sharia Council Number 04/DSN-MUI/IV/2000, which states that to help the community to improve their welfare and various activities, Islamic banks need to have murabaha facilities for those who need them, namely selling an item by confirming the price buy it to the buyer and the buyer pays it at a higher price as profit.

The Sharia Business Unit strengthens BTN's determination to make work a component of worship that cannot be separated from other worship. Furthermore, Bank BTN Sharia Business Units are called "BTN Syariah" with the motto "Forward and Prosper Together". Sharia Business Units are overseen by the Sharia Supervisory Board (DPS), which advises the Directors, Heads of Sharia Divisions, and Heads of Sharia Branch Offices on matters related to Sharia principles. In November 2004, the P.T. BTN Sharia branch office was organized, with the head of the branch reporting to the head of the Sharia division .

They were followed on February 25, 2005, by the opening of the Bandung KCS. Then on March 17, 2005, the Surabaya KCS was opened consecutively on the 4th and April 11, 2005, Yogyakarta KCS and Makassar KCS, and in December 2005, the Malang and Solo KCS were opened. In 2007, Bank BTN operated 12 (twelve) Sharia Branch Offices and 40 Sharia Service Offices (Office Channeling) in branch and conventional sub-branch offices spread across Jakarta, Bandung, Surabaya, Yogyakarta, Makassar, Malang, Solo, Medan, Batam, Tangerang, Bogor, and Bekasi. These Sharia branch offices can operate on-time-real-time thanks to adequate information technology support. Implementing the concept of a murabaha contract in mortgage financing that occurs at BTN KCPS Pekalongan, namely customers visiting BTN KCPS Pekalongan to finance the purchase of a house, then bank BTN KCPS Pekalongan provides financing with a predetermined and mutually agreed upon amount. The customer seeks and contacts the developer himself to determine the purchase of the house, after which the customer returns the mortgage financing loan in agreed instalments or instalments along with interest.

The writer will use the terms of sale and purchase to review the contract. The first concerns the pillars of buying and selling. Reginald's research is on his thesis entitled "Analysis of Murabahah Housing Financing Contracts in Sharia BTN (KPR Syariah) According to Islamic Contract Law," banks buy and sell from developers on behalf of customers. However, this is irrelevant, even though the writer obtained interview data with a bank employee. There are several reasons why this matter cannot be allowed. The first fact is that banks must fully serve customers, not customers who are required to act as bank representatives to transact with developers .

The second essential is that the buyer carries out a sale and purchase to the developer/developer but not as a representative, the buyer does it for himself, and the buyer carries out a loan agreement with the bank. If the buyer is a representative, the customer cannot make an advance payment to the developer/developer. Then, if the buyer is a representative of the bank, therefore the buyer is not allowed to carry out price negotiation transactions without an order from the bank as the representative.

The collateral trading system that BTN Syariah runs is: Financing contracts are not buying and selling, and BTN Syariah does not collect any margin on the financing agreement. Scholars agree that all debts with margin/interest are usury. For example, Ibnul Mundzir said, "The Ulama agree that if someone is in debt by requiring 10% of the debt as a gift or addition, then he lends it by taking the additional is usury" .

They are judging from the legal terms of sale buying, namely buying and selling goods that are not personal property. Then the status of the house becomes abnormal because the item is a problem. Does the bank already own it and then sold to the buyer? In the wakalah contract agreement between the buyer and the bank, there is a clause stating that the buyer under the wakalah contract must submit the house and documents to the bank and the bank obtains the house together with the above documents in principle. However, this clause is meaningless because it is in Article 3 concerning It is states that the bank distributes the rights to the customer to sign a sale and purchase agreement with the developer/seller on behalf of the customer and the bank pays the seller the purchase price of the house, the customer after signing the KPR BTN Platinum I.B. financing contract.

The principle of the BTN Sharia KPR method is compliance with the wakalah contract, which is closer to the fact that the bank sells goods that are not legally owned yet. Merging a wakalah contract with a murabaha contract is permissible, but fulfills all the pillars and conditions of wakalah and murabahah. However, Islamic banks are unwilling to comply because they require taking risks usually taken by the general transaction industry, so the customer will likely cancel the order. Therefore, Islamic banks cannot carry out contracts for the sale of commodities as they usually do now. From the point of view of the terms of sale and purchase on credit, you can buy and sell on credit as long as the conditions are met. Not related to factors that are not allowed. However, the ability to buy and sell instalments must pay attention to the requirements.

CONCLUSION

KPR at BTN KCPS Pekalongan applies several financing concepts, namely the istishna contract financing concept and the murabahah contract financing concept. Implementing the concept of a murabahah contract for mortgage financing that occurs at BTN KCPS Pekalongan, namely customers coming to BTN KCPS Pekalongan to finance the purchase of a house, then the BTN KCPS Pekalongan bank provides financing with a predetermined and mutually agreed amount. This happened at BTN KCPS Pekalongan, namely the customer came to the BTN KCPS Pekalongan bank to submit a house order, and then the BTN KCPS Pekalongan bank contacted the developer to order the house according to the criteria specified by the customer. Then the BTN KCPS Pekalongan bank contacted the customer to make a transaction that the house already exists, the customer must pay a down payment (D.P.) as a receipt to the BTN KCPS Pekalongan bank.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses his gratitude for the support of this research from all parties, both from researchers at the Faculty of Islamic Religion, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Indonesia and Human Resources & School of Management Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University Hyderabad, India. Hopefully, this research collaboration can be continued to the next stage.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally to the main contributor to this paper, some are as chairman, member, financier, article translator, and final editor. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

M. Mutamimah and P. L. Saputri, “Corporate governance and financing risk in Islamic banks in Indonesia,” J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res., 2022. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIABR-09-2021-0268.

M. S. Apriantoro and N. R. Wijayanti, “Bibliometric Analysis of Research Directions in Islamic Bank In The Pandemic Period,” NISBAH J. Perbanka Syariah, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 127–137, 2022. https://doi.org/10.30997/jn.v8i2.6408.

M. S. Apriantoro, S. G. Maheswari, and H. Hudaifah, “Islamic Financial Research Directions During Pandemic: A Bibliometric Analysis,” At-Taradhi J. Stud. Ekon., vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 75–97, 2022. https://doi.org/10.18592/at-taradhi.v13i2.7174.

M. H. Bilgin, G. O. Danisman, E. Demir, and A. Tarazi, “Economic uncertainty and bank stability: Conventional vs. Islamic banking,” J. Financ. Stab., vol. 56, p. 100911, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2021.100911.

K. A. WIBOWO, A. G. ISMAIL, A. TOHIRIN, and J. SRIYANA, “Factors Determining Intention to Use Banking Technology in Indonesian Islamic Microfinance,” J. Asian Finance. Econ. Bus., vol. 7, no. 12, pp. 1053–1064, 2020. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no12.1053.

W. Jauhari and M. D. A. Khan, “Implementation of The Concept of’Urf and Maslahah in Buying and Selling Gold With Non-Cash Payment (Comparative Study of Fatwa DSN-MUI and Fatwa Al-Lajnah Ad Dāimah Li Al-Buhūṡ Al-‘Ilmiyyah Wa Al-Iftā’Saudi Arabia),” SUHUF, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 54–65, 2023. https://doi.org/10.23917/suhuf.v35i1.22638.

R. Ismal, “An optimal risk-return portfolio of Islamic banks,” Humanomics, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 286–303, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1108/H-08-2013-0055.

S. Daly and M. Frikha, “Islamic Finance: Basic Principles and Contributions in Financing Economic,” J. Knowl. Econ., vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 496–512, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-014-0222-7.

M. Syahbandir, W. Alqarni, M. A. Z. Dahlawi, A. Hakim, and B. Muhiddin, “State Authority for Management of Zakat, Infaq, and Sadaqah as Locally-Generated Revenue: A Case Study at Baitul Mal in Aceh,” Al-Ihkam J. Huk. dan Pranata Sos., vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 554–577, 2022. https://doi.org/10.19105/al-lhkam.v17i2.7229.

M. A. Rachman, “Halal Industry in Indonesia: Role of Sharia Financial Institutions in Driving Industrial and Halal Ecosystem,” Al-Iqtishad J. Ilmu Ekon. Syariah, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 35–58, 2019. https://doi.org/10.15408/aiq.v11i1.10221.

D. Andrews and A. C. Sánchez, “The evolution of homeownership rates in selected OECD countries: Demographic and public policy influences,” OECD J. Econ. Stud., pp. 207–243, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_studies-2011-5kg0vswqpmg2.

A. Muhtarom, “Implementasi Akad Murabahah Pada Produk Pembiayaan Kredit Pemilikan Rumah (KPR) di Bank Syariah Mandiri KC Bojonegoro Menurut Hukum Ekonomi Syariah,” … Magister Huk. Ekon. Syariah, 2019. https://doi.org/10.30651/justeko.v3i1.2960.

K. Hanim Kamil, M. Abdullah, S. Shahimi, and A. Ghafar Ismail, “The subprime mortgage crisis and Islamic securitization,” Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Finance. Manag., vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 386–401, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1108/17538391011093315.

I. Erol and K. Patel, “Housing Policy and Mortgage Finance in Turkey During the Late 1990s Inflationary Period,” Int. Real Estate Rev., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 98–120, 2004. https://doi.org/10.53383/100055.

R. M. Yusof, M. Bahlous, and H. Tursunov, “Are profit sharing rates of mudharabah account linked to interest rates? An investigation on Islamic banks in GCC Countries,” J. Ekon. Malaysia, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 77–86, 2015. https://doi.org/10.17576/JEM-2015-4902-07.

A. Budiono, “Penerapan Prinsip Syariah Pada Lembaga Keuangan Syariah,” Law Justice, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 54–65, 2017. https://doi.org/10.23917/laj.v2i1.4337.

M. Iqbal, “Konsep Uang Dalam Islam,” J. Ekon. Islam Al-Infaq, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 294–317, 2012. [Online]. Available: https://www.jurnalfai-uikabogor.org/index.php/alinfaq/article/view/359.

H. Sarvari, A. Mehrabi, D. W. M. Chan, and M. Cristofaro, “Evaluating urban housing development patterns in developing countries: A case study of Worn-out Urban Fabrics in Iran,” Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 70, p. 102941, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102941.

B. W. P. Muhammad Diaz Arda Kusuma, “Deconcentration Funds: Redistribution and Economic Growth in Indonesian Provinces,” in The 19th Malaysia Indonesia International Conference on Economics, Management and Accounting (MIICEMA), 2018, pp. 1689–1699. https://feb.untan.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/4.pdf

Y. M. Rahman, R. S. Bachro, E. H. Djukardi, and U. Sudjana, “Digital Asset/Property Legal Protection in Sharia Banking Financing and its Role in Indonesian Economic Development,” Int. J. Crim. Justice Sci., vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 149–161, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://ijcjs.com/menu-script/index.php/ijcjs/article/view/57.

R. Ismal, “Assessing the gold Murabahah in Islamic banking,” Int. J. Commer. Manag., vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 367–382, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCoMA-05-2012-0034.

A. Bakhouche, T. El Ghak, and M. Alshiab, “Does Islamicity matter for the stability of Islamic banks in dual banking systems?” Heliyon, vol. 8, no. 4, p. e09245, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09245.

Sutrisno and A. Widarjono, “Maqasid sharia index, banking risk and performance cases in Indonesian Islamic banks,” Asian Econ. Finance. Rev., vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 1175–1184, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.aefr.2018.89.1175.1184.

F. Asni, M. S. I. Ishak, and M. D. H. Yasin, “Penalty for Late Payment: The Study of Shariah Risk in Islamic Housing Products in Malaysia,” Glob. J. Al-Thaqafah, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 28–44, 2022. https://doi.org/10.7187/GJAT122022-3.

L. Saqib and A. U. Turabi, “The concept of 1stisna’ in Islamic commercial law (shari’a) and its possible role in the development of local farming in Pakistan,” Hamdard Islam., vol. 42, no. 1–2, pp. 83–105, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://hamdardislamicus.com.pk/index.php/hi/article/view/7.

M. Hanif, “Islamic mortgages: principles and practice,” Int. J. Emerg. Mark., vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 967–987, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-02-2018-0088.

D. N. Musjtari, F. S. R. Roro, and R. Setyowati, “Islamic P2p Lending As An Alternative Solution For The Unfair Conventional Platform In Indonesia,” Uum J. Leg. Stud., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 21–43, 2022. https://doi.org/10.32890/uumjls2022.13.1.2.

D. G. J. and F. U. Noor Mahmudah1, Iswanto1, Dian M Setiawan1, “Analysis Demand and Supply Parking Lot of Motorcycle Abu Bakar Ali Yogyakarta,” in International conference of sustainable innovation, 2019, pp. 37–39. https://doi.org/10.2991/icosite-19.2019.26.

Rudiana, “Transaksi Dropshipping Dalam Perspektif Ekonomi Syari’ah,” 2015. [Online]. Available: https://www.syekhnurjati.ac.id/jurnal/index.php/al-mustashfa/article/view/457.

O. Diallo, T. Fitrijanti, and N. D. Tanzil, “Analysis of the influence of liquidity, credit and operational risk, in Indonesian Islamic bank’s financing for the period 2007-2013,” Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 279–294, 2015. https://doi.org/10.22146/gamaijb.8507.

J. Dean, “Muslim values and market value: A sociological perspective,” J. Islam. Mark., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 20–32, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-02-2013-0013.

M. S. Apriantoro, “Islamic Law Perspective in the Application of My Pertamina as a Non-Cash Payment System and Control of Fuel Subsidy Flow,” J. Transcend. Law, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 71–80, 2022. https://doi.org/10.23917/jtl.v4i1.19976.

C. Williams, “Research Methods,” J. Bus. Econ. Res., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 65–72, 2007. https://doi.org/10.19030/jber.v5i3.2532.

Imam Gunawan, Metode Penelitian KUALITATIF. 2016, pp. 1–27. [Online]. Available: http://ap.fip.um.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/metod-kualitatif.pdf

Samsu, Metode Penelitian (Teori & Aplikasi Penelitian Kualitatif, Kuantitatif, Mixed Methods, serta Research and Development), no. July. Jambi: Pustaka Jambi, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343162238_Metode_Penelitian_Teori_Aplikasi_Penelitian_Kualitatif_Kuantitatif_Mixed_Methods_serta_Research_and_Development.

M. I. H. Kamaruddin, S. M. Auzair, M. M. Rahmat, and N. A. Muhamed, “The mediating role of financial governance on the relationship between financial management, Islamic work ethic and accountability in Islamic social enterprise (ISE),” Soc. Enterp. J., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 427–449, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-11-2020-0113.

N. Nurmila, “Indonesian Muslims’ discourse of husband-wife relationship,” Al-Jami’ah, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 61–80, 2014. https://doi.org/10.14421/ajis.2013.511.61-79.

H.-J. Kim and B. Hudayana, “What Makes Islamic Microfinance Islamic? A Case of Indonesia’s Bayt al-Māl wa al-Tamwīl,” Stud. Islam., vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 31–54, 2022. https://doi.org/10.36712/sdi.v29i1.17862.

R. Calder, “Halalization: Religious Product Certification in Secular Markets,” Sociol. Theory, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 334–361, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275120973248.

Muthoifin, “Pembinaan Kerukunan Masyarakat Baru Pada Perumahan Baru Perum Griya Salaam Boyolali,” in The 10th University Research Colloqium 2019 Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Kesehatan Muhammadiyah Gombong, 2019, pp. 12–15. [Online]. Available: http://repository.urecol.org/index.php/proceeding/article/view/823.

B. M. A. M. H. A.-N. Nurul Hakim, “Ethics of Buying and Selling Online Sharia Economic Perspective: Study of the Concept of Iqâlah,” Demak Univers. J. Islam …, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 18–25, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/deujis.v1i01.22.

M. S. Apriantoro, “The Epistemology of Ushul Fiqh Al-Ghazali In His Book Al-Mustashfa Min Ilmi al-Ushul,” Profetika J. Stud. Islam, vol. 2, no. 22, 2021. https://doi.org/10.23917/profetika.v22i2.16668.

Islahulhaq, W. Wibowo, and I. D. Ratih, “Classification of non-performing financing using logistic regression and synthetic minority over-sampling technique-nominal continuous (SMOTE-NC),” Int. J. Adv. Soft Comput. its Appl., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 115–128, 2021. https://doi.org/10.15849/IJASCA.211128.09.

M. S. Nasir, Y. Oktaviani, and N. Andriyani, “Determinants of Non-Performing Loans and Non-Performing Financing level: Evidence in Indonesia 2008-2021,” Banks Bank Syst., vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 116–128, 2022. https://doi.org/10.21511/bbs.17(4).2022.10.

S. A. R. Nur Sillaturohmah Handayani, Sya’roni, “General Property Rights from Sharia Perspective: Strategy for the Implementation of Ummah’s Economic Welfare and Justice,” Demak Univers. J. Islam Sharia, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 49–58, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/deujis.v1i01.18.

N. K. Putra and A. Amrin, “Consumption from an Islamic Economic Perspective: Study of Quranic Verses on Consumption,” Demak Univers. J. Islam …, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 33–38, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/deujis.v1i01.21.

A. A. Itsna Nur Muflikha, Sya’roni, “Investment Of Sharia Shares In Indonesia Stock Exchange Representative In Sharia Law Economic Perspective,” Demak Univers. J. Islam Sharia, vol. 01, no. 1, pp. 24–32, 2023. https://doi.org/10.61455/deujis.v1i01.25.

Downloads

Submitted

Accepted

Published

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Muhamad Subhi Apriantoro, Eis Rantika Puspa, Dandi Ibtihal Yafi, Deast Amanda Putri; Rozi Irfan Rosyadi

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.